Portraits in Oversight:

Joint Committee

on the Conduct of the Civil War

“We are here armed with the whole power of both houses of Congress. They have made it our duty to inquire into the whole conduct of the war; into every department of it. We do not want to do anything that will result in harm or wrong. But we want to know what to do, and we must know if we can, what is to be done, for the country is in jeopardy.”

Senator Benjamin Wade, December 26, 1861

During the Civil War, from December 1861 to May 1865, the U.S. Congress convened a special joint investigative committee to inquire “into the whole conduct of the war.” Led by Republicans but with bipartisan support, the committee spent nearly four years compiling evidence, holding hearings, issuing reports, and demanding reforms. This sustained oversight effort produced the country’s most detailed record of the conflict, exposed military incompetence and wrongdoing, condemned slavery and racial injustice, and reinforced traditions of fact-based, bipartisan oversight by Congress.

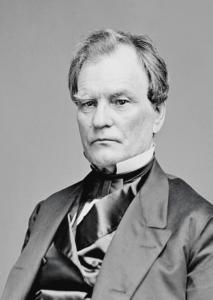

The committee’s origins lie in an early major defeat of the Union Army. On July 21, 1861, Republican senators Benjamin Franklin “Bluff” Wade (Ohio), Zachariah Chandler (Michigan), Henry Wilson (Massachusetts), and James Grimes (Iowa), joined spectators at a picnic lunch overlooking the Battle of Bull Run. They were horrified to see Union troops, who had fared well in the morning, retreating towards them at a run as Confederate reinforcements caused a rout. Senators Wade and Chandler attempted to block the road and even threatened to shoot soldiers who fled, but failed to stop the retreat.

The senators stewed over the army’s abysmal performance, which was followed by a series of Union defeats throughout the summer and fall. They became increasingly convinced that the North’s problems stemmed from indecisive military leadership and a misguided president. Senators Wade and Chandler, the most radical abolitionists in Congress, grew more outraged when, following General John C. Frémont’s emancipation of slaves in Missouri on August 30, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln revoked the Frémont proclamation. Frémont had reasoned that if slaves were considered the property of traitors, they qualified as war contraband which he could unilaterally confiscate as general in command of Missouri. President Lincoln’s refusal to support Frémont’s reasoning was condemned by both Senators.

When the 37th Congress convened three months later on December 2, 1861, the two Senators called for the legislature to investigate the conduct of the war. On December 5, Senator Chandler introduced a resolution to investigate the defeats at Bull Run and Ball’s Bluff, but many senators viewed it as too narrow. Senator Grimes then proposed that all aspects of the war be subject to congressional oversight, an approach that carried the day. Of the 39 Republicans and other minor party members in the Senate, 33 voted for the resolution. In addition, seven of the ten Democrats remaining in the Senate – many Southern Democrats had left or been expelled from Congress when their states seceded from the Union – also voted in favor. The Senate resolution moved to the House which passed it unanimously without debate on December 10, 1861, creating the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War.

The joint committee was comprised of three senators and four representatives, some of whom were replaced during the course of the committee’s work:

- Chairman: Senator Benjamin Wade (Republican, Ohio)

- Senator Zachariah Chandler (Republican, Michigan)

- Representative John Covode (Republican, Pennsylvania) – Replaced in 1863 by Representative Benjamin Loan (Unionist, Missouri)

- Representative Daniel Gooch (Republican, Massachusetts)

- Representative George Julian (Republican, Indiana)

- Senator Andrew Johnson (Democrat, Tennessee)

- Replaced by Senator Joseph Wright (Democrat, Indiana) in March 1862 upon his appointment to Military Governor of Tennessee

- Replaced in 1863 by Senator Benjamin Harding (Democrat, Oregon)

- Representative Moses Odell (Democrat, New York)

“While there is agitation in the public mind…and no inquiry is made and no step is taken to enlighten the public in relation to the matter…shall we, who are agents of that public, be told that during its progress, be it longer or shorter, we are to ask no questions, make no complaints, no investigations, know nothing, say nothing, and inquire nothing about it? We are not under the command of the military of this country. They are under ours as a Congress, and I stand here to maintain it.”

Senator William Pitt Fessenden during debate to establish the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

Although the Republicans held a substantial majority on the committee – as they did in the full Congress following the secession of the Southern states – the Democratic minority was also influential in a way not seen on other committees. In fact, Democratic Representative Odell was one of the most active committee members, often traveling to obtain witness testimony.

The committee wasted no time getting started. At its first meeting on December 20, 1861, the members elected Senator Wade as chair and began planning their work. Investigative topics included the defeat at Bull Run, the removal of General Frémont from command in Missouri, and the idleness of the Army of the Potomac. The committee voted unanimously in favor of motions asking Generals George B. McClellan and Frémont to appear for interviews.

The committee’s rapid pace continued for nearly four years, holding a total of 272 committee meetings (164 during the 37th Congress and 108 in the 38th) and publishing four reports which covered multiple investigations and ran thousands of pages. Many of the committee’s meetings took place outside of the nation’s capital, as members traveled around the country to take testimony. The committee decided early on that a quorum was not required, so it became rare for all members to be present at a hearing or business meeting. The committee also agreed that their work would remain secret until complete and prohibited those called to testify from sharing with third parties any details of the hearings. At the same time, committee members were often accompanied by a stenographer on their trips to question witnesses, and subsequent published reports provided important Civil War data that might otherwise have been lost to history.

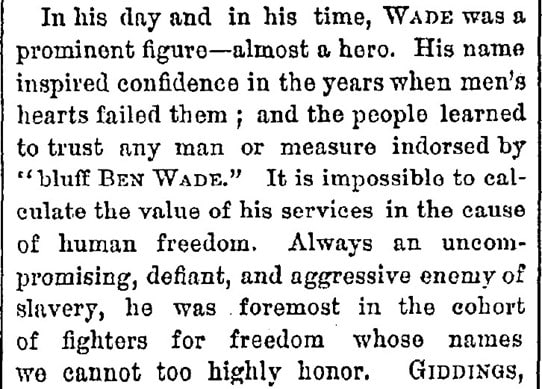

The committee’s most progressive members were Chair Wade and Senator Chandler who were focused not only on military operations, but also on issues related to slavery and racial discrimination. Their leadership led to detailed inquiries into military defeats and barbaric treatment of African American troops. Highly critical of Senator Wade’s radicalism while alive, the New York Times wrote upon his death:

Eulogies offered on the Senate floor upon the death of Senator Chandler included this tribute: “Of all the great men who have lived and died in this generation, there was no keener seer, no shrewder organizer, no franker partisan, no truer patriot.” In 1913, the state of Michigan further honored him by selecting Senator Chandler for one of the two statues the state was allowed to place in the U.S. Capitol.

The committee’s work was shaped not only by its leadership, but also by official requests for inquiries. On December 4, 1862, for example, in response to a House request, the committee visited and reported on subpar conditions at a military hospital camp, “Camp Convalescent,” in Alexandria, Virginia. Following the excursion, a subcommittee met with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to insist on building suitable accommodations, discharging men too injured or sick to resume fighting, and appointing an inspector to survey military hospitals and ensure proper conditions. In 1863, following a motion by Senator J.M. Wilkinson of Minnesota to investigate the disastrous battle at Fredericksburg, the committee released a 40-page report exposing military infighting and leadership failures. On May 6, 1864, at the request of Brigadier General Henry C. Hoffman, the committee traveled to Annapolis, Maryland to see the sick, malnourished, and abused prisoners of war released by the Confederacy. The committee issued a damning report on the mistreatment of those prisoners complete with shocking photographs.

The Committee on the Conduct of the War initially worked amicably with the executive branch, and its members were described by President Lincoln’s personal secretaries as “always earnest, patriotic, and honest.” As the war dragged on, however, the committee began to challenge the more moderate president who rarely heeded its advice. Despite that conflict, the evidence indicates that committee members were never denied meetings with the president, cabinet members, or military officers, and their requests for documents were virtually always fulfilled, setting important precedents for executive branch cooperation with congressional oversight.

As explained in the committee’s 1863 report on the Army of the Potomac, the members saw themselves as investigators and advisors to the president:

“Your committee therefore concluded that they would best perform their duty by endeavoring to obtain such information in respect to the conduct of the war as would best enable them to advise what mistakes had been made in the past and the proper course to be pursued in the future; to obtain such information as the many and laborious duties of the President and his cabinet prevented them from acquiring, and to lay it before them with such recommendations and suggestions as seemed to be most imperatively demanded.”

Civil War expert Fergus Bordewich wrote that “[t]he committee became, in many respects, the driving engine of congressional war policy, prodding and pressuring the president toward more decisive action against slavery and more aggressive military action.”

The committee enjoyed relative popularity within Congress and the public, but not with military officers, most of whom dreaded being called to testify. Over time, hundreds of the most important figures in the Union’s military appeared before the committee. It was a common belief among the public and the committee that one decisive victory would destroy the Confederacy and win the war. In October 1861, for example, Senator Chandler wrote to his wife that “We can win a victory in 24 hours if only our generals will fight.” That conviction led to frequent committee criticism of military leaders. In return, military officers often resented the civilian committee members – none but Representative Loan, who joined the committee in the 38th Congress, had any military experience – questioning the committee’s motives, analysis, and recommendations.

The committee released reports throughout its four years on almost every aspect of the Civil War, from trade issues to military campaigns. Despite the wide range of topics and differing political ideologies among committee members, almost every report was agreed upon unanimously. One exception was a report on General Frémont’s handling of the army in the West. Representatives Gooch and Odell did not sign it, as they believed the evidence was incomplete, but they did endorse the testimony it contained.

Critics have pointed out that the committee’s interrogation of military witnesses was often unfair. Although most committee members were lawyers, and Chair Wade was a judge, the committee often treated military officers with hostility. This approach was, in part, because several members deeply mistrusted graduates of West Point, as most of its 200 graduates from southern states had defected to the Confederate army. The witnesses were not allowed to employ legal counsel, invoke their Fifth Amendment rights, or face their accusers. Committee members frequently asked leading questions and solicited hearsay evidence, then used the evidence against the officers before them. Decades later, witnesses asked federal courts to clarify under what circumstances constitutional and procedural rights in jury trials should also constrain congressional hearings.

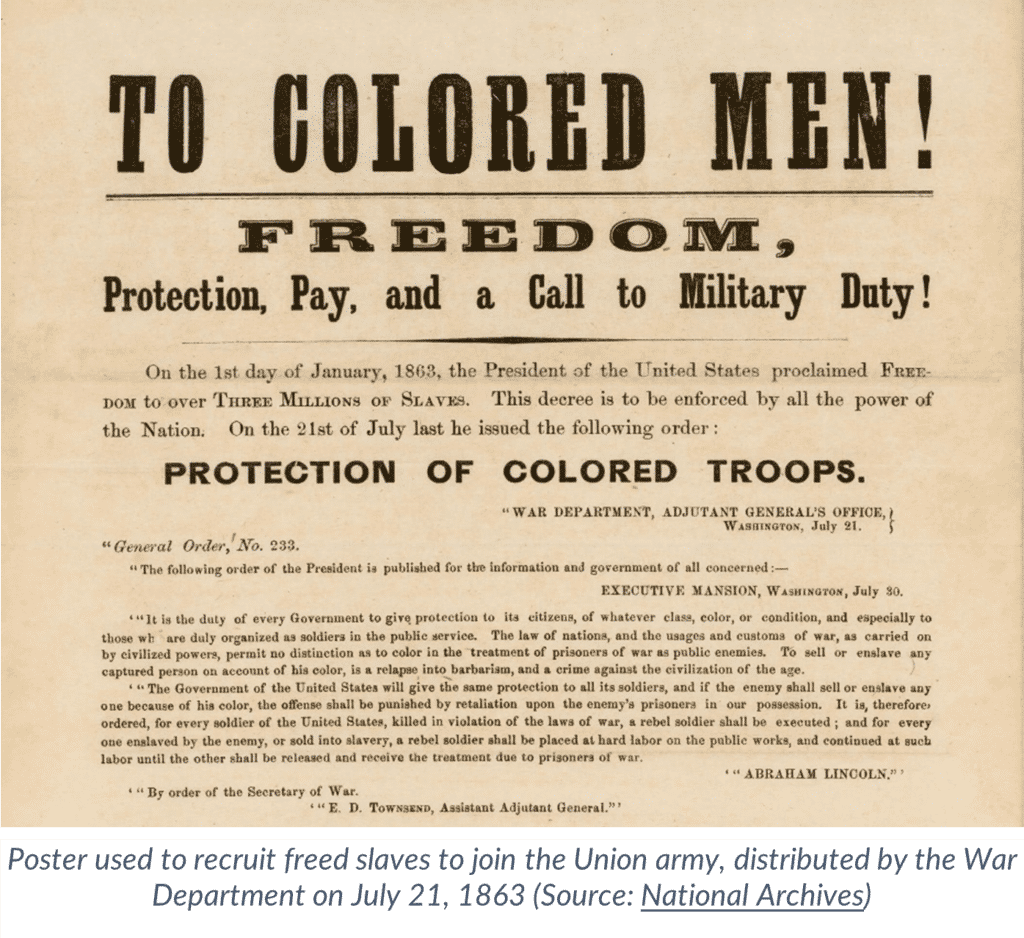

The abolition of slavery, as well as poor recruitment and mistreatment of African American soldiers were important issues to the committee which used its hearings and reports to expose brutal practices and rank injustice. The committee’s work was instrumental in Congress’ passing the second Confiscation Act and the Militia Act on July 17, 1862. The former confiscated slaves from Southerners, deeming them “captives of war … and forever free.” The latter authorized President Lincoln to enlist African Americans in the military for any position they were qualified to fill. Equally important, the committee became the fiercest enforcer of these laws, taking reluctant generals to task for not enlisting able African American men and advocating for the promotion of those who did enlist.

The Fort Pillow Massacre on April 12, 1864, led to an explosive committee report that was widely published and drew public outrage. Fort Pillow in Tennessee had been guarded by about 600 Union soldiers, almost half African American. Captured during an attack by at least 1,500 Confederate troops, almost half the Union soldiers were killed, many while surrendering or fleeing. Over half of the African American soldiers were killed, as well as some civilians, including children. Survivors reported seeing African Americans hacked with sabers, beaten to death, buried alive, disemboweled, or burned alive. Some were nailed to the floor of a building that was then set on fire. The committee’s report used first-hand accounts and other evidence to show that, as Chair Wade wrote, “it is the intention of the rebel authorities not to recognize the officers and men of our colored regiments as entitled to the treatment accorded by all civilized nations to prisoners of war.” The ensuing public outcry pressured President Lincoln into withdrawing from prisoner exchange agreements with the South. In addition, the report helped build public appreciation for the bravery and sacrifices of African American troops and support for legislation to end slavery and protect civil rights.

Another event severely condemned by the committee was the Sand Creek Massacre on November 29, 1864, when U.S. soldiers brutally attacked a community of Native Americans in the Colorado Territory. Although this matter did not involve conflict between Union and Confederate troops, because it took place during the Civil War the committee conducted an inquiry into the facts and issued a report detailing what happened. The report disclosed that the massacred tribes had not committed any offense or violence, were friendly with American settlers and authorities, and flew the American flag and a white flag to communicate that they were peaceful, yet were attacked without warning.

While the number of casualties varies among sources, the committee wrote in its report that the massacre resulted in “more than one hundred dead bodies, three-fourths of them of women and children.” After describing troop movements leading to the Native American campsite, the report describes the scene as follows:

“And then the scene of murder and barbarity began – men, women, and children were indiscriminately slaughtered. In a few minutes all the Indians were flying over the plain in terror and confusion …. From the sucking babe to the old warrior, all who were overtaken were deliberately murdered. Not content with killing women and children, who were incapable of offering any resistance, the soldiers indulged in acts of barbarity of the most revolting character …. It is difficult to believe that beings in the form of men, and disgracing the uniform of United States soldiers and officers, could commit or countenance the commission of such acts of cruelty and barbarity as are detailed in the testimony.”

The atrocities described by witnesses in testimony before the committee horrified the public, cast blame squarely on the military, and exonerated the Native Americans. The government promised financial and land reparations to the survivors of the massacre, but has yet to fulfill that pledge.

The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War upheld and advanced the country’s tradition of taking a hard look at its military, exposing problems and wrongdoing, and demanding change. It also became a vehicle for Congress to condemn slavery, racial discrimination, and mistreatment of African American soldiers. The committee’s hearings and reports – often described or reprinted in newspapers and distributed widely – educated the public and influenced national policy, including setting the stage for the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments outlawing slavery and enshrining the right of all Americans to equal protection under the law. Moreover, the committee further cemented the right of Congress to investigate the executive branch and the military, even during the nation’s worst crises.

“Upon the ‘conduct of the present war’ depended the issue of the experiment inaugurated by our fathers, after so much expenditure of blood and treasure – the establishment of a nation founded upon the capacity of man for self-government.”

Report of the Committee on the Conduct of the War, Volume One introduction (1863)

Learn More

- A History of Notable Senate Investigations (U.S. Senate Historical Office)

- Congress at War: How Republican Reformers Fought the Civil War, Defied Lincoln, Ended Slavery, and Remade America by Fergus M. Bordewich

- Congress Investigates: A Critical and Documentary History, Volume One, Chapter Six by the Robert C. Byrd Center

- The Crucible: The pivotal relationship between Lincoln and the abolitionists

- Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

- Tap, B. (1996). “These devils are not fit to live on God’s earth”: War crimes and the Committee on the Conduct of the Civil War, 1864 – 1865. Civil War History, 42(2), 116 – 132. https://doi.org/10.1353/cwh.1996.0051

- Tap, B. (2002). Amateurs at war: Abraham Lincoln and the Committee on the Conduct of the War. Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, 23(2), 1-18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20149029