Portraits in Oversight:

General St. Clair's Defeat

The very first oversight investigation undertaken by the U.S. Congress occurred in 1792, just three years after the U.S. Constitution took effect. The inquiry delved into a significant U.S. military defeat, while also setting important precedents for future congressional oversight investigations.

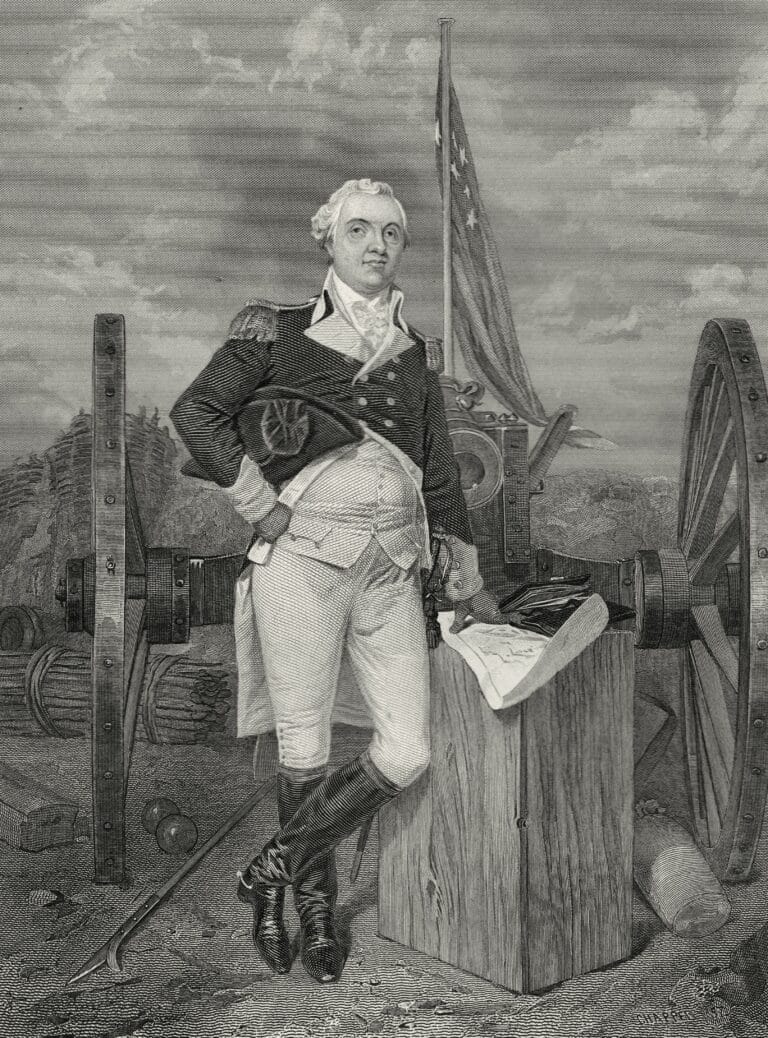

At the time, the newly formed United States was expanding westward, and settlers in the Northwest Territory increasingly came into conflict with Native Americans living there. In 1791, Congress authorized a new regiment to address the conflicts and provided funding to enlist militia for six months. President George Washington appointed Arthur St. Clair, Governor of the Northwest Territory, to serve as Major General of the new regiment and tasked him with designing and executing an effective battle plan.

Problems arose from the start. General St. Clair placed responsibility for recruitment in the hands of Brigadier General Richard Butler, but the low pay made recruiting soldiers difficult. Prisons were emptied to fill the ranks. Secretary of War Henry Knox had appointed Samuel Hodgdon as Quartermaster General for the military; Mr. Hodgdon signed procurement contracts with a prominent but deceitful businessman named William Duer. Duer’s failure to furnish necessary items slowed the expedition at every step:

- Uniforms and equipment were not provided on time, if at all, and were of low quality.

- Shipments of guns and gunpowder were delayed or failed to arrive.

- Lack of tools and subpar axe blades slowed construction of Forts Hamilton and Jefferson.

- Quartermaster General Hodgdon and contractor Duer did not hire enough boats to transport troops down the Ohio River.

- Duer did not provide most of the horses he had contracted to furnish, and the people he hired had no experience caring for the animals, so many died.

- Quartermaster General Hodgdon and Brigadier General Butler were supposed to meet General St. Clair at Fort Washington by July 15, 1791, but did not arrive until September – by which point, General St. Clair and his men were already marching north.

- Rations were scarce and desertions were common as the weather grew worse.

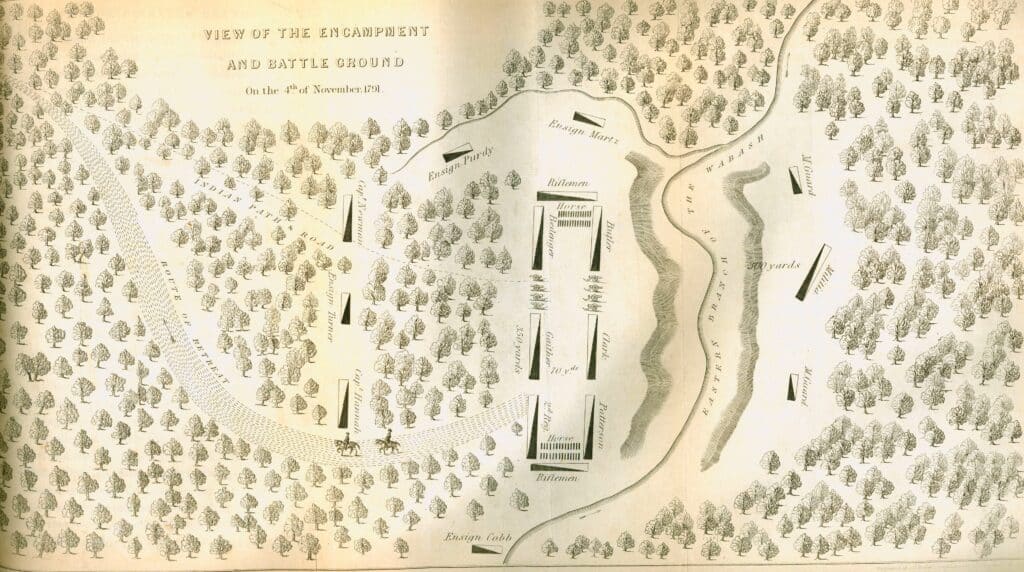

The regiment moved slowly through present-day Ohio, in part because of the weather, but also due to dense wilderness that had to be cleared and the need to build bridges across streams to transport carts and cannons. Throughout the expedition, General St. Clair received regular messages from Secretary Knox relaying President Washington’s disappointment in the mission delays. It was not until the evening of November 3, 1791, that the regiment made it to its final destination on the banks of the Wabash River – months later than anticipated. Due to the late hour of arrival, General St. Clair did not order the troops to put up standard fortifications.

As the troops prepared breakfast the next morning, 1,000 Native Americans from the Shawnee, Miami, and Delaware tribes, led by War Chiefs “Little Turtle” (Mihšihkinaahkwa) of the Miami tribe and “Blue Jacket” (Weyapiersenwah) of the Shawnee tribe, descended on the camp. Many of the volunteer militia fled, and though some soldiers tried to stand and fight, Little Turtle’s forces overwhelmed General St. Clair’s artillery and surrounded the regiment. After two hours of brutal attack, General St. Clair commanded the surviving troops to retreat 29 miles south to Fort Jefferson. What would become known as the Battle of the Wabash was the worst defeat of U.S. forces by Native Americans in U.S. history. Over 650 U.S. soldiers were killed, including Brigadier General Butler, and more than 270 were wounded, including at least 70 casualties among camp followers. Native Americans suffered approximately 100 casualties.

The defeated army returned to Fort Washington by midday November 8, and General St. Clair sent a letter to War Secretary Knox with news of the battle. A furious President Washington was informed of the defeat on November 9. The next day, Secretary Knox reported to Congress that the late season and poorly trained soldiers were to blame for the terrible defeat.

In December 1791, General St. Clair arrived in Philadelphia to meet with the President and Secretary Knox. He asked for a court-martial to determine the reasons for the loss, hoping it would exonerate him in the eyes of the press and public, and added that following the proceedings he would submit his resignation. Two days later, President Washington informed him that an insufficient number of officers with a rank comparable to his own made a court-martial impossible and accepted his resignation.

In the House of Representatives, a motion to form a committee to investigate the military defeat was made on February 2, 1792. On March 27, 1792, Virginia Representative William Branch Giles introduced a resolution requesting an inquiry by President Washington to uncover the cause of the calamity. And so began the debate that would spark the first congressional investigation in the nation’s history.

Because the Constitution is silent on the power of Congress to conduct oversight, the members of the Second Congress had to determine what authority, if any, they possessed to investigate another branch of government and how to proceed. The debate included several Founding Fathers then serving in the House of Representatives. Aware that their actions would set a precedent for future congressional oversight, many members of Congress weighed in.

- Delaware Representative John Vining rejected the notion of asking the President to investigate. He argued that if someone was found to have neglected their duties, they must be impeached, and since the power to impeach belongs to the House, so must the power to investigate.

- New Jersey Representative Abraham Clark (Declaration of Independence signatory) noted that clear public interest into what had gone wrong required an inquiry. He observed that the motion merely asked the President to investigate in whatever way he felt was appropriate. He noted that if the President did not think that he should be the one to investigate, he could so inform the House.

- South Carolina Representative William Smith expressed the concern that this type of investigation would violate the constitutional separation of powers, because the military was part of the executive branch.

- North Carolina Representative Hugh Williamson (Constitution signatory) was unsure if the House had authority to investigate the President, and suggested forming a committee to examine disbursements of public funds during the military operation, as spending issues certainly fell within congressional purview.

- Georgia Representative Abraham Baldwin (Constitution signatory) stated that the only way forward was to establish a House committee that could gather information and present it to the President along with recommendations.

- Virginia Representative and future President James Madison (Constitution signatory) argued that the resolution asked the President to do something he could not accomplish. The inquiry, he asserted, was essentially a court-martial, but because so many officers were hundreds of miles away in the Northwest Territory, they would be unable to testify.

At the conclusion of the debate, Representative Giles’ resolution to request an inquiry from President Washington was defeated 35 to 21. Pennsylvania Representative Thomas Fitzsimons (Constitution signatory) then moved to establish a special House committee to investigate the matter. The measure passed 44 to 10. Representative Fitzsimons was named Chair of the committee that also included Representatives Giles, Vining, Clark, John Francis Mercer of Maryland, Theodore Sedgwick of Massachusetts, and John Steele of North Carolina. Three days later, on March 30, 1792, the committee made its first request for documents from War Secretary Knox. Knox, in turn, sent the request to the President with a letter asking permission to submit the documents to Congress.

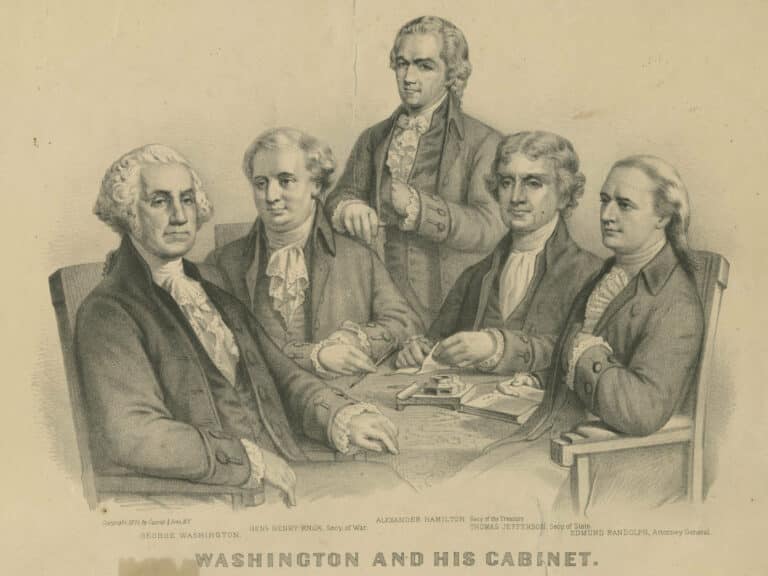

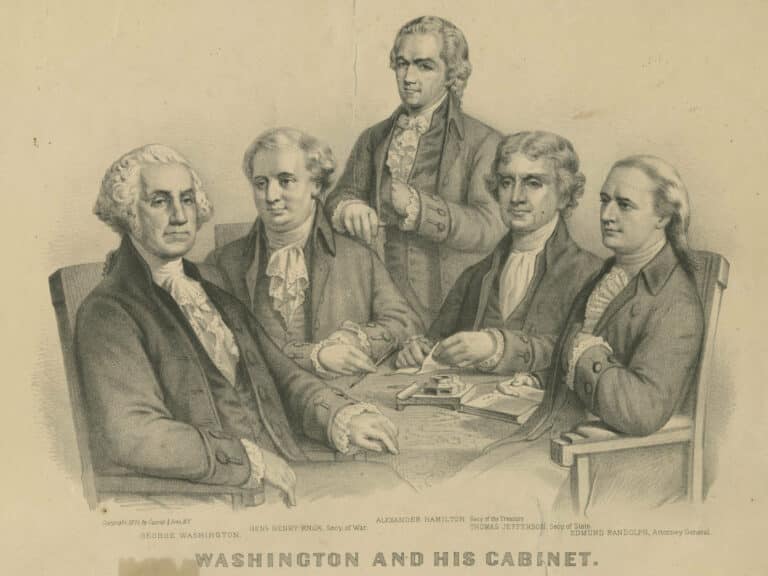

President Washington, aware that his actions would set a precedent, requested a meeting with his “department heads” (now known as Cabinet officers) on Saturday, March 31, 1792, to determine the appropriate response to the committee’s requests. The department heads – Knox, Secretary of State and future President Thomas Jefferson of Virginia (author of the Declaration of Independence), Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton of New York (Constitution signatory and author of the Federalist Papers), and Attorney General Edmund Jennings Randolph of Virginia (member of the Constitutional Convention) – then left to consider the matter. According to notes by Secretary Jefferson, when they returned on Monday, April 2, they were all in agreement:

First, that the House was an inquest, and therefore might institute inquiries. Second, that it might call for papers generally. Third, that the Executive ought to communicate such papers as the public good would permit, and ought to refuse those, the disclosure of which would injure the public: consequently were to exercise a discretion. Fourth, that neither the committee nor House had a right to call on the Head of a Department, who and whose papers were under the President alone; but that the committee should instruct their chairman to move the House to address the President.

These notes make clear that both branches of government believed Congress had the authority to investigate government actions. The statement that the President should provide records “as the public good would permit” also created the basis for executive privilege that still exists today. Despite this privilege, President Washington decided that he would allow the committee access to all requested documents, but that the originals could not be taken from the departments. Instead, a clerk from the House watched as copies were prepared and checked their accuracy. President Washington also permitted the department heads to testify before the committee.

The House committee held several days of public hearings. Along with the department heads, several military officers testified. General St. Clair not only attended most days, he testified, provided his personal papers to the committee, and submitted a full account of his recollection of events in evidence that topped 50 pages. The committee also examined records from the Departments of War and Treasury.

After taking testimony and reviewing the evidence, the committee drafted and issued Congress’ first oversight report. The report, which exceeded 100 pages in final form, concluded that Brigadier General Butler had not failed in his responsibilities to recruit an adequate number of troops, but that transportation of those troops had been delayed due to “the gross and various mismanagements and neglects in the quartermaster’s and contractor’s departments.” The report found no sufficient reason for Quartermaster General Hodgdon, appointed in March, to have remained in Philadelphia until June 4, and delayed arrival at Fort Washington until September 10, 1791. In the meantime, the report found that General St. Clair had been forced to perform the duties of quartermaster in addition to his own. The report concluded that General St. Clair had “discharged the various duties which devolved upon him, with ability, activity, and zeal.”

The committee report noted that General St. Clair had testified that he had heard from many suppliers that they had not been paid, even though $70,000 had been advanced to contractor Duer to secure the necessary goods and services. The report also questioned why the War Department told General St. Clair and Butler that no funds were available for needed supplies, but used only about $576,000 of the $653,000 appropriated for the regiment. It also criticized Secretary Knox for failing to send funds for pay until after many soldiers had already been discharged.

The committee report concluded that the principle causes of the military failure were:

- delays in procuring supplies and materials;

- mismanagement and neglect by the Quartermaster and contractor Duer; and

- lack of experienced and disciplined troops.

Official records marking the committee vote on the final report have not survived, but General St. Clair, who attended the key hearing, recorded in his observations that the report was unanimously accepted.

Because the committee finished its report after the first session of the Second Congress adjourned, it was taken up when the second session commenced in November 1792. A lively debate ensued over a motion to request Secretaries Knox and Hamilton to appear during the next day’s session to respond to issues raised in the report. The next day, however, a lengthy letter from Secretary Knox asked that he be allowed to address the House to counter report statements damaging his reputation. The committee decided to reconvene to examine the new evidence, with slight personnel changes: Vining, Mercer, and Sedgwick stepped down, and Pennsylvania Representative William Findley joined. Witnesses included Secretary Knox, Quartermaster General Hodgdon, General St. Clair, Inspector of the Army Francis Mentges, Brigadier General Josiah Harmar, and Major David Zeigler. In response to the testimony, the committee made some revisions to its report, but the general conclusions remained the same.

On February 26, 1793, the report was formally presented to the House, and the investigative committee was dissolved. The committee’s work spurred several changes. First, Quartermaster General Hodgdon was removed from his position in the War Department, demonstrating that Congress could hold an executive official accountable for mismanagement. Second, battle lessons learned led to administrative reforms producing a more centralized, well-trained, and logistically supported U.S. military.

Equally important, this early precedent, acknowledged by senior members of both the legislative and executive branches, made clear that Congress had the authority to investigate actions taken by the federal government, acquire executive agency documents, take sworn testimony, and produce a report with detailed factual findings and recommendations. The 1792 investigation of General St. Clair’s Defeat led the way for government oversight by every Congress to come.

Learn More

- A Narrative of the Manner of the Campaign Against the Indians Under the Command of General St. Clair, by Major General St. Clair (1812)

- In 1812, after years of urging the House to publish its work, General St. Clair published the committee report himself along with the account he had submitted to the committee, notes he took during the hearings, and letters he sent and received during the expedition.

- Congressional Inquiries are Nearly as Old as the Constitution

- Remembering General St. Clair’s Defeat

- Clair’s Campaign of 1791: A Defeat in the Wilderness That Helped Forge Today’s U.S. Army

- Congress Investigates: A Critical and Documentary History, Volume One, Chapter One by the Robert C. Byrd Center