Portraits in Oversight:

Congress Investigates

KKK Violence During Reconstruction

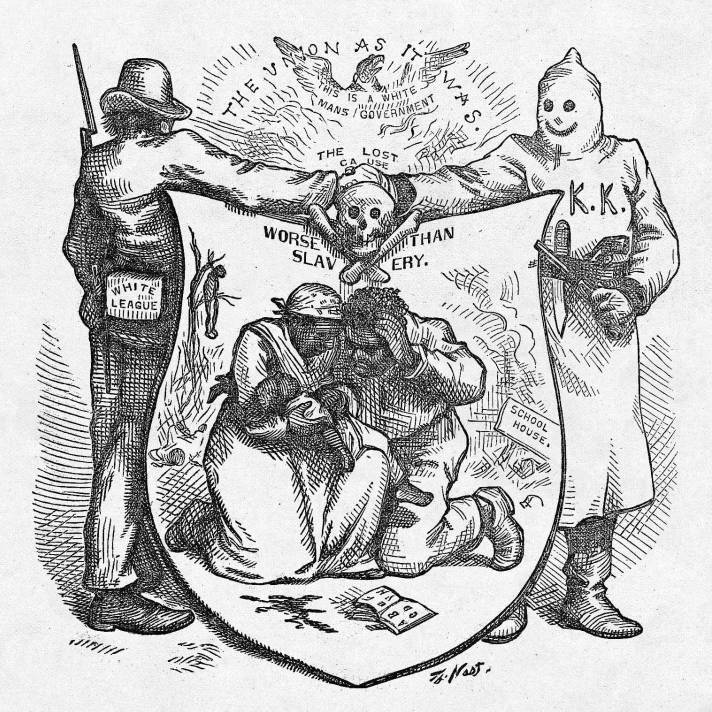

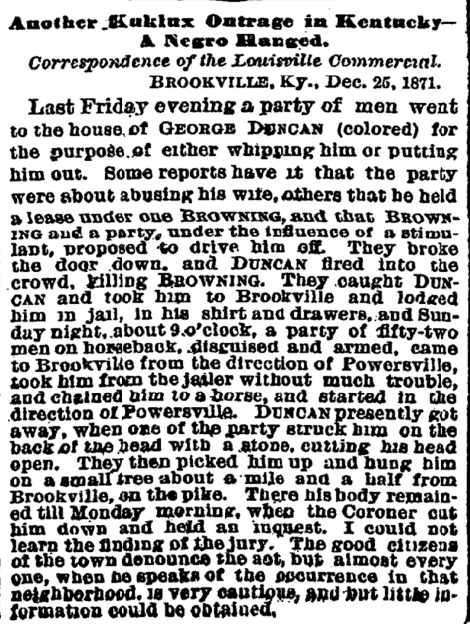

The end of the Civil War marked the beginning of radical change in the United States with the country taking action to recover from years of war, recognize the rights of four million formerly enslaved people, and protect African Americans from a violent backlash against their new status. During the 1870s, in a period now known as Reconstruction, Congress launched two extensive investigations into a frightening new organization, the Ku Klux Klan, exposed how it was terrorizing African Americans and their political allies in the South, and supported legislative and administrative actions to curb its brutality and lawlessness.

The post-Civil War period was a time of great turmoil. Congress enacted laws that represented the most significant advances in civil rights since the nation’s founding. They included the 1865 ratification of the 13th Amendment banning slavery and the 1866 passage of the Civil Rights Bill and the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, giving all Americans the right to due process and equal protection under the law. In 1869, led by the Republican party, Congress passed the 15th Amendment, ultimately ratified in 1870, securing the right to vote regardless of race.

As a result of the new laws, African Americans flooded onto the voter rolls. At the beginning of 1867, less than 1% of African American men were registered to vote. By the end of 1867, 80% had registered.[1]

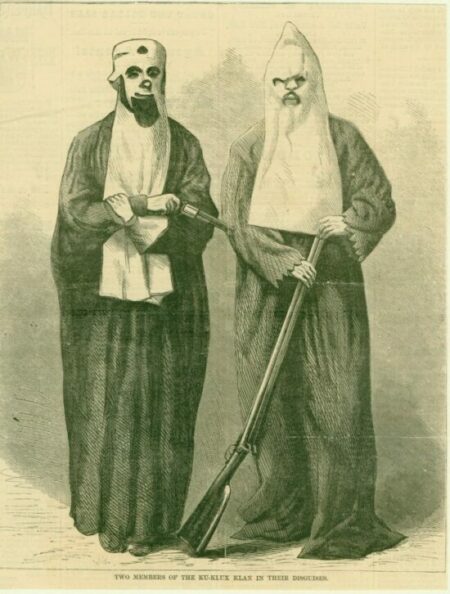

At the same time, racial violence in the former Confederate states accelerated. Many attributed the escalating violence to the growing strength of the Ku Klux Klan, a secretive organization formed in Pulaski, Tennessee, in 1866, by former Confederate soldiers. KKK members were targeting not only African Americans but also pro-Reconstruction Republican candidates seeking office in the 1868 presidential and congressional elections.[2] In 1870, to stop KKK members from committing crimes while cloaked in hoods and robes, Congress enacted the Enforcement Act to make it illegal “to band or conspire together or go in disguise” upon a public highway or private premises to violate another’s constitutional rights.[3]

To better gauge the extent and reasons for the rising racial violence in the South, Congress decided to form an investigative committee to dig into the facts. On January 19, 1871, with support from then President Ulysses S. Grant, the Senate passed a resolution creating the Select Committee to Investigate Alleged Outrages in the Southern States.

Vice President Schuyler Colfax appointed five Republican and two Democratic Senators to the committee: Republicans John Scott of Pennsylvania (chair), Zachariah Chandler of Michigan, James W. Nye of Nevada, Benjamin F. Rice of Arkansas, and Henry Wilson of Massachusetts; and Democrats Thomas E. Bayard, Sr. of Delaware and Francis Preston Blair, Jr. of Missouri. Because the committee started its work near the end of the congressional session, the members decided to focus attention on KKK activity in North Carolina due to reports of egregious acts of brutality terrorizing African American communities in that state.[4]

The committee took testimony from 29 Republicans and 21 Democrats, including six KKK members. The majority report, approved by the five Republican committee members, found that, in North Carolina, the KKK was essentially a paramilitary white supremacist organization that “sought to carry out its purpose by murders, whippings, intimidations, and violence, against its opponents.”[5] The majority report also found that KKK members committed crimes in bands and used disguises, secrecy, and perjury to avoid punishment. In contrast, the two Democratic members of the committee declared that the committee had found no evidence of the KKK’s existence and blamed “carpetbaggers” – a derogatory term used to describe persons who moved South to help the freed slaves and build the Republican Party – for the disagreements between African Americans and white Southerners.[6]

During the course of the committee’s deliberations and despite internal disagreements over the existence and role of the KKK in racial violence, on February 28, 1871, Congress enacted the Second Force Act. This law was designed to strengthen the earlier anti-KKK law in anticipation of the upcoming congressional elections.[7]

Though the select committee’s inquiry lasted less than two months, in that time, the senators received multiple requests to investigate additional KKK violence from the bi-racial Republican governments of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. In recognition of those requests, the committee’s majority report recommended that the Senate decide whether further investigation of the KKK was necessary.[8] For his part, President Grant wrote to Speaker of the House James G. Blaine, urging Congress to take further action to deal with violence in the South.

On March 15, 1871, by a vote of 126 to 64, the House adopted a resolution establishing its own select committee to investigate the KKK.[9] However, heated debate erupted the next day because, while some Republicans felt that further investigation was a fair compromise between different factions of the party, other Republicans believed the Senate committee had already proven the existence of KKK violence and legislative action should be taken immediately. Rep. Horace Maynard of Tennessee declared: “[I]f this Congress, with its Republican majority, shall adjourn without taking some action and making some effort to put a stop to those outrages it will be a crime against humanity of the darkest character.”[10] Sympathizing with that position, Rep. Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts and Rep. Samuel Shellabarger of Ohio resigned from the newly established House committee.

In response, on March 17, 1871, Senate Republicans passed a concurrent resolution creating a Joint Select Committee with members from both the Senate and House.[11] Republicans had a much larger majority in the Senate than the House (75% versus 54% of the seats[12]) which meant a joint investigation would balance the committee in their favor. Considerable time during debate was also spent on how to ensure that the investigation of the KKK would be conducted fairly and impartially. It was decided that subcommittees, which would gather most of the testimony on KKK activity, must include at least one member from each party. Sen. Allen G. Thurman, a Democrat from Ohio, stressed: “no attempt should be made to pervert an investigation that ought to be solely in the interest of the whole country and all the people of the country, into an investigation having for its object the advantage of this party or that party.”[13]

After slight amendments to the enabling resolution, the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States was formally established on April 10, 1871. Its charge was “to inquire into the condition of affairs in the late insurrectionary States, so far as it regards the execution of the laws, and the safety of the lives and property of the Citizens of the United States.”[14] While the resolution did not explicitly name the KKK, all understood that the inquiry would focus on the Ku Klux Klan and other violent white supremacist groups active in the South including the White League, Knights of the White Camellia, and Red Shirts.

The committee, composed of seven senators and 14 representatives, began with the same seven senators who had served on the Senate Select Committee, though Sens. Wilson and Nye were later replaced by fellow Republicans Daniel D. Pratt of Indiana and John Pool of North Carolina. House Speaker Blaine appointed Republican Reps. Luke P. Poland of Vermont (chair of the House members), Charles W. Buckley of Alabama, John Coburn of Indiana, Burton C. Cook of Illinois, William E. Lansing of New York, Horace Maynard of Tennessee, Glenni W. Scofield of Pennsylvania, and Job E. Stevenson of Ohio; and Democrats James B. Beck of Kentucky, Samuel S. Cox of New York, James C. Robinson of Illinois, Philadelph Van Trump of Ohio, Daniel W. Voorhees of Indiana, and Alfred M. Waddell of North Carolina. Reps. Buckley and Cook were later replaced by John F. Farnsworth of Illinois and Benjamin Butler, and Rep. James M. Hanks of Arkansas took the place of Rep. Voorhees.[15]

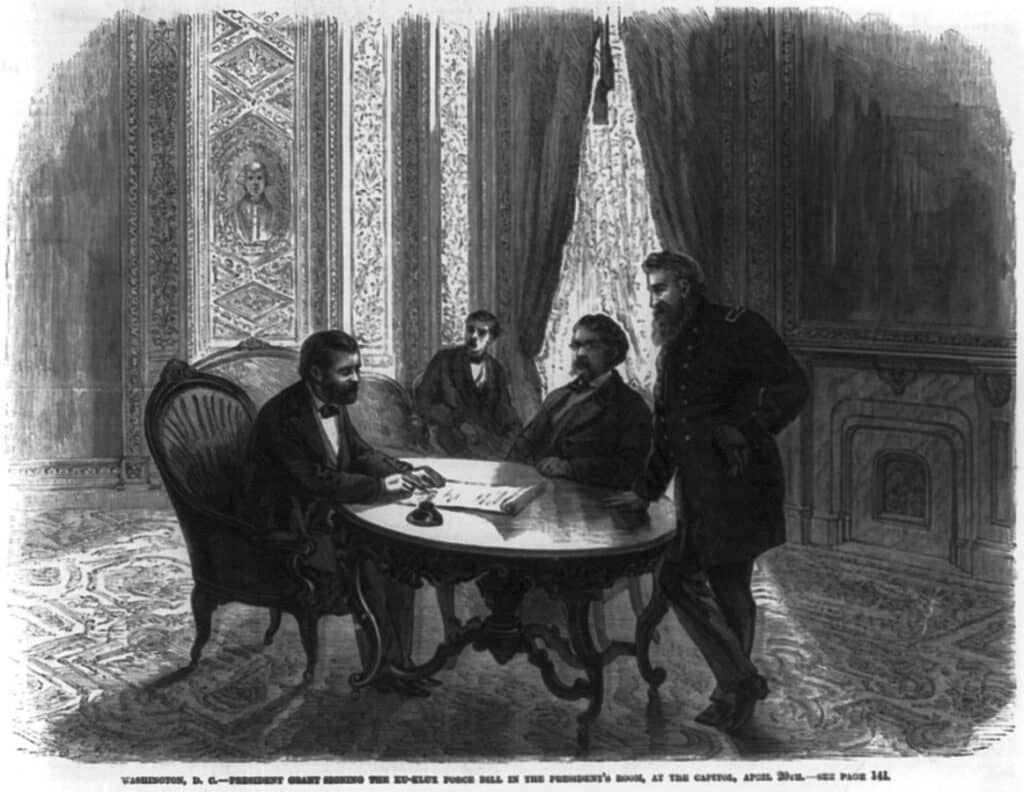

The committee met for the first time on April 20, 1871, the same day that President Grant signed into law the Third Force Act. Popularly known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, it gave the president authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, deploy military or militia forces, or use “other means, as he deems necessary” in the Southern states if “any person or any class of persons” is denied “equal protection” or “equal privileges or immunities under the laws.”[16]

The Joint Select Committee’s first action was to appoint seven members to a subcommittee that would chart a course of action for the inquiry.[17] On May 17, 1871, the committee formed a second subcommittee to examine the “debts and taxes” of the former Confederate states. That subcommittee collected testimony and evidence until the end of July, when it recessed. In mid-September, the full committee reconvened and formed two more subcommittees to travel to the South and take testimony about the KKK and racial violence plaguing the region. Sen. Bayard and Reps. Lansing, Maynard, Scofield, Voorhees were sent to Florida, Georgia, and North and South Carolina. Sens. Pratt, Rice, and Blair and Reps. Buckley and Robinson went to Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee.[18]

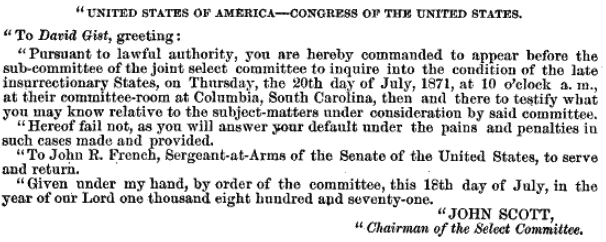

In December 1871, the committee confronted a novel parliamentary question when KKK members Clayton Camp and David Gist failed to appear when subpoenaed by one of the subcommittees, and when W. L. Saunders refused to testify so as not to incriminate himself. Earlier laws stated that witnesses could be held in contempt by “either” House, but no U.S. or English parliamentary precedent offered guidance on how to handle a contempt action involving two legislative bodies. Because the joint committee issued the key subpoenas, Congress had to rule on how this type of contempt should be handled. After debate, the Senate passed a Senate resolution issuing an arrest warrant for all three individuals for contempt of Congress. Asher C. Hinds, Clerk of the House of Representatives, later explained in a compilation of congressional precedent:

“[T]he two Houses possessed individually the power to punish …. The original form of the resolution merely amounted to the Senate asking the consent of the House of Representatives to punish a contempt against itself. A punishment in the Senate would not be a bar to subsequent punishment in the House. If the Senate required the aid of the House to lay hold on the witness, the Senate’s powers would be too slender to deal with him after his arrest.”[19]

The 10-month House-Senate investigation produced over 13,000 pages of reports, testimony, and documents collected and published in 13 volumes. A total of 586 witnesses testified, including African American men and women who spoke at significant risk to themselves and their families, white Republicans, ex-Confederate generals, and members of the KKK. To this day, it is cited by scholars as one of the most valuable sources of information on Southern life in the Reconstruction era. Despite criticism of the witness demographics – 376 of those called to testify were white men – historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr. offered this analysis of the congressional investigation: “The United States never had a truth and reconciliation commission after slavery ended. The Klan hearings were as close as we came. It was extraordinary. Congress was actually listening to black people testifying about the atrocities committed against them.”[20]

The majority report, signed by every Republican member of the committee, placed blame for the rising Southern racial violence squarely on the Ku Klux Klan:

“The proceedings and debates in Congress show that, whatever other causes were assigned for disorders in the late insurrectionary States, the execution of the laws and the security of life and property were alleged to be most seriously threatened by the existence and acts of organized bands of armed and disguised men, known as Ku-Klux.”[21]

The majority report determined that formal acknowledgement of African American rights had spurred violent individuals to organize and form the KKK. While the report found that the 13th and 14th Amendments “were not the causes of the organization,” they, as well as the Force Acts and ratification of the 15th Amendment, “were met with increased bitterness” and were seen to be “imposed by the usurpation and tyranny of Congress.” The report stated that KKK leaders used the laws as a rallying cry and they “became the pretext for crimes and lawlessness that, unchecked, could end only in anarchy.”[22]

The majority report detailed outrages committed by the KKK against African Americans and Southern Republicans, traced the reach of the organization into every Southern state, and described how the KKK was terrorizing Southern communities:

“[The KKK] rode into Eutaw, Alabama, and murdered Boyd for seeking to punish by law the murderers of colored men. It pursued the ministers of the Methodist Episcopal Church in that State because of their loyalty. In North Carolina it hung Wyatt Outlaw, for no other offense than opposition to the Ku-Klux, and barbarously whipped Mr. Justice for exercising his political rights. In South Carolina it tortured Elias Hill for preaching the gospel to his race, for educating their children, for leading them in their political and business life. It assembled a force, armed and disguised, to prevent the execution of a writ of habeas corpus in Union County, issued to secure ten negroes charged with murder for lawful trial, and hanged them without trial. In Mississippi it destroyed schoolhouses and drove away schoolteachers. In Georgia, and indeed in all the States examined into, it committed murders, whippings, and outrages so numerous and so horrible that one of the retained defenders of the perpetrators has honored his own nature and announced the existence of these enormities by declaring that, in South Carolina, ‘they are shocking to humanity; they admit neither justification nor excuse; they violate every obligation which law and nature impose upon men.’”[23]

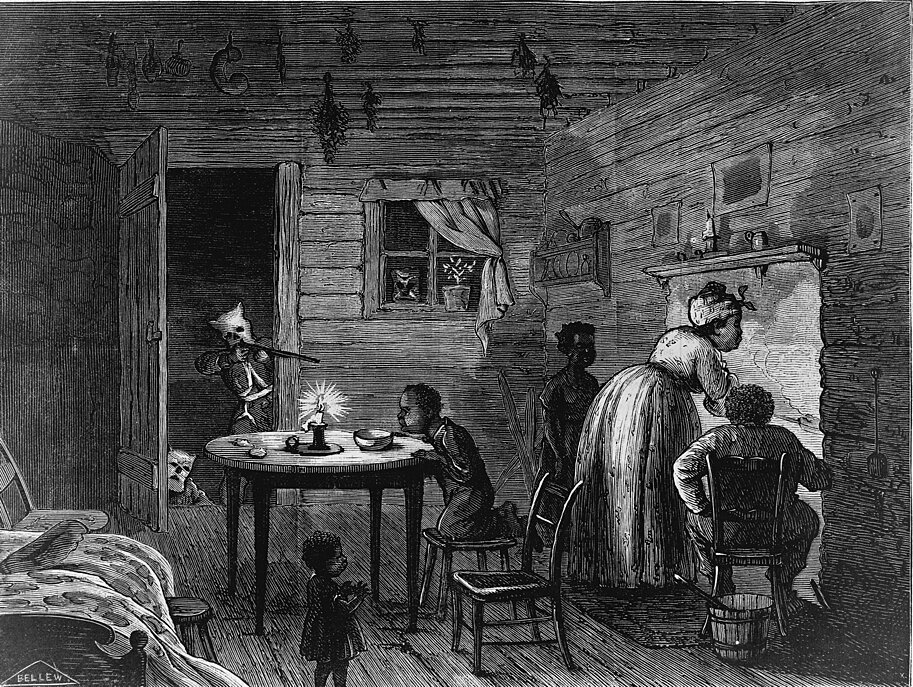

Among the 8,000 pages of testimony included with the report, multiple African American witnesses described the violence they experienced at the hands of the KKK. Essie Harris, for example, testifying before the committee in Washington, D.C., on July 1, 1871, described the second time the KKK visited his home:

“They were there, I reckon, an hour and a half. They said they had killed me. I felt it to be life and death anyhow. I thought my wife and children were dead; I did not expect anything else. The shot just rained like rain…. They said they were going to set my house on fire; that they did not intend to leave there till they had done it.”[24]

Although sexual violence perpetrated by the KKK was largely glossed over in witness accounts, Mr. Harris relayed an instance of sexual assault in his testimony, said that type of assault had been “very common,” and “[t]hey say that if the women tell anything about it, they will kill them.”[25] In addition to describing attacks against African Americans, the report presented evidence that the KKK directed politically motivated violence against white Republicans who supported civil rights. The report included, for example, this testimony by James M. Justice, a white Republican and general assemblyman, at a circuit court trial at Raleigh, North Carolina:

“Immediately on seeing me one man approached and said, ‘O, you damned radical, we have you at last;’ and they took hold of me by the right arm and seized my throat, and pulled me through into the entry, and as I approached the entry where stood the others, they commenced beating me with their fists…. They asked me if I was not ashamed of being of that party that put negroes to rule and govern. They said the white men would not suffer such things; that I had been warned; that my course would no longer be borne by the whites of this country; that they had brought me there to put me to death.”[26]

The joint committee’s minority members did not support the majority report’s findings and issued their own analysis. The minority report was three times as long as the majority report and signed by all of the committee Democrats. It acknowledged that some men in the Southern states came together “in secret organization,” but contended the men acted to protect themselves and their families from the oppressive laws of the federal government, rather than to deny the civil rights of other citizens. The minority report also denounced the Ku Klux Klan Act and President Grant’s suspension of habeas corpus in South Carolina counties. The report was littered with racist observations, such as the following statement by Rep. Van Trump:

“It was an oft-quoted political apothegm, long prior to the war, that no government could exist ‘half slave and half free.’ The paraphrase of that proposition is equally true, that no government can long exist ‘half black and half white.’ If the republican party, or its all-powerful leaders in the North, cannot see this, if they are so absorbed in the idea of this newly discovered political divinity in the negro, that they cannot comprehend its social repugnance or its political dangers … why then ‘farewell, a long farewell” to constitutional liberty on this continent.’”[27]

Although the final two reports of the Joint Select Committee drew very different conclusions, the committee’s journal reflects bipartisan interactions during the course of the investigation. As the Senate had dictated in its initial formation of the joint committee, testimony was taken only when a member of each party was present. One subcommittee responsible for examining the debts and taxes of the Southern states benefited from the joint analysis of two Republicans and a Democrat. The trio met twice in September for “consultation and an interchange of views”[28] as they wrote up their findings. At a third and final meeting, they “unanimously agreed upon a report to be submitted to the joint select committee.”[29] Another subcommittee appointed to secure certain documentation from state governments also included two Republicans and a Democrat. They met 18 times between November 1 and December 2, 1871, to conduct an “examination of reports, consultation, and an interchange of views.”[30]

In the end, the Joint Select Committee struck hardest at the KKK not through legislation, but through the media. Because its hearings were public and the committee printed tens of thousands of copies of its reports and testimony, newspapers throughout the nation frequently printed excerpts. Exposing the KKK’s secret operations and bringing light to the violence it wrought throughout the South made it more difficult for courts and state governments to dismiss individual attacks by the KKK as anomalies.[31] The inhumane acts detailed in the factual evidence assembled by the committee also made it increasingly untenable to deny the KKK’s existence or justify its actions.

Still another consequence of the congressional investigations was the creation of a powerful new agency to prosecute wrongdoing by KKK members. Although the Attorney General had existed as a Cabinet position in the United States since 1789, the Attorney General had never been supported by a specific agency. In June 1870, President Grant appointed Amos T. Akerman as his new Attorney General and, on July 1, 1870, created the Department of Justice to assist him in protecting African American voting rights. Attorney General Akerman, a former Confederate officer and slaveholder, had joined the Republican party immediately after the Civil War and, as a U.S. district attorney, prosecuted many voter intimidation cases. He explained his political shift as follows:

“Some of us who had adhered to the Confederacy felt it to be our duty when we were to participate in the politics of the Union, to let Confederate ideas rule us no longer…. Regarding the subjugation of one race by the other as an appurtenance of slavery, we were content that it should go to the grave in which slavery had been buried.”[32]

Fortified by the newly ratified amendments and Force Acts, Attorney General Akerman and his fledgling department prosecuted hundreds of KKK members. His biographer, William McFeely, wrote: “Perhaps no attorney general since his tenure … has been more vigorous in the prosecution of cases designed to protect the lives and rights of black Americans.”[33]

At a time when violence was rife against African Americans and white Republicans across the South and disputes over the KKK were raging, Congress conducted two investigations that not only carefully documented Ku Klux Klan atrocities, but also helped justify new laws to protect American rights, prompted formation of the U.S. Department of Justice, and spurred mass prosecutions of individual KKK members. While Congress’ actions did not vanquish the KKK, its inquiries compiled critical evidence that publicly exposed the KKK’s white supremacist origins and built a historical record that continues to help delegitimize the organization today.

[1] Marchesi, J. (Director). (2019). Reconstruction: America after the Civil War [Film]. PBS.

[2] Burns, R. A., Hostetter, D. L., & Smock, R. W. (2011). Congress investigates: A critical and documentary history (2nd edition). Infobase Publishing, p. 302.

[3] Burns et al., 2011, p. 306

[4] Burns et al., 2011, p. 306.

[5] Burns et al., 2011, p. 307.

[6] Burns et al., 2011, p. 307.

[7] Burns et al., 2011, p. 308.

[8] Burns et al., 2011, p. 308.

[9] Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 1st Sess. (1871), p. 117. https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lwcglink.html

[10] Cong. Globe, 1871, p. 126.

[11] Cong. Globe, 1871, p. 135.

[12] Congressional directory, 42nd Cong. (1871).

[13] Cong. Globe, 1871, p. 135.

[14] U.S. Congress. (1872). Report of the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States. (Cong. Rpt. 141-1), p. 1.

[15] Burns et al., 2011, p. 312.

[16] Enforcement Act of 1871. Pub. L. No. 42-22 17 Stat. 13 (1871). https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llsl//llsl-c42/llsl-c42.pdf

[17] Burns et al., 2011, p. 313.

[18] Burns et al., 2011, p. 313.

[19] Hinds, A. C. (1907, March 4). Hinds’ precedents of the House of Representatives of the United States including references to provisions of the Constitution, the laws, and decisions of the United States Senate. Government Printing Office, p. 73 – 74. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-HPREC-HINDS-V3/pdf/GPO-HPREC-HINDS-V3.pdf

[20] Marchesi, 2019.

[21] Cong. Rpt. 141-1, p. 83.

[22] Cong. Rpt. 141-1, p. 83.

[23] Cong. Rpt. 141-1, p. 83 – 84.

[24] Cong. Rpt. 141-2, p. 89-90.

[25] Cong. Rpt. 141-2, p. 100.

[26] Cong. Rpt. 141-2, p. 417-419.

[27] Cong. Rpt. 141-1, p. 516.

[28] Cong. Rep. 141-1, p. 609.

[29] Cong. Rep. 141-1, p. 609.

[30] Cong. Rep. 141-1, p. 615 – 618.

[31] Burns et al., 2011, p. 318.

[32] Greene, B. (2020, July 1). Created 150 years ago, the Justice Department’s first mission was to protect black rights. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/created-150-years-ago-justice-departments-first-mission-was-protect-black-rights-180975232/

[33] Greene, 2020.

Learn More

- Report of the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States(13 volumes, over 13,000 pages)

- Report on the Alleged Outrages in the Southern States by the Select Committee of the Senate(March 10, 1871)

- The Enforcement Acts of 1870 – 1871

- Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871

- Reconstruction in America: Racial Violence After the Civil War 1865 – 1876, A Visual Reading Guide

- Created 150 Years Ago, the Justice Department’s First Mission Was to Protect Black Rights