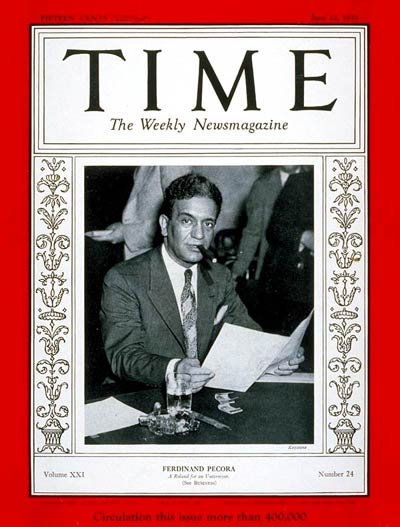

Portraits in Oversight:

Ferdinand Pecora

and the 1929 Stock Market Crash

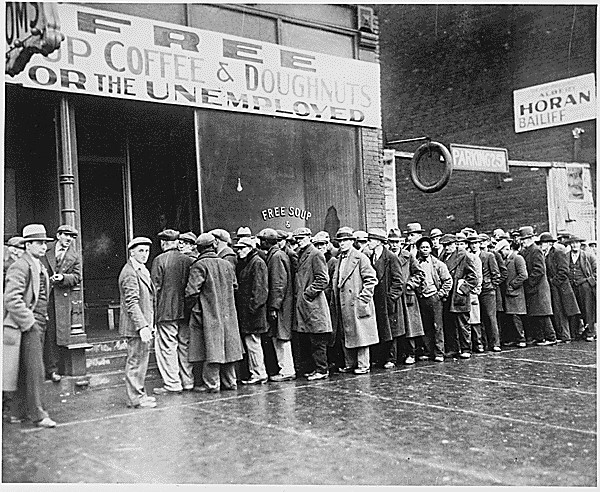

Congressional members of both parties spent the years following the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression attempting to investigate the causes of the financial devastation, with little success until the advent of the Pecora Investigation in 1933. An earlier inquiry had been undertaken by the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency which was initially chaired by Senator Peter Norbeck, a Republican from South Dakota, and whose vice chair was Duncan Fletcher, a Democrat from Florida. The two reversed roles in 1932, when Republicans lost the Senate majority, and Franklin D. Roosevelt won the presidency for the first time.

The Banking Committee inquiry into the stock market had been authorized in 1932 (Senate Resolutions 84 and 234), but didn’t pick up steam until the committee hired its fourth chief counsel, Ferdinand Pecora, a former prosecutor, in January 1933. The committee had earlier focused on the practice of short selling stocks, but failed to obtain key bank records and held ineffective hearings that failed to attract public or media attention. When Mr. Pecora was hired to write the committee’s final report, he was alarmed by how narrow and incomplete the investigation was. He asked committee members to reopen the inquiry, and the Senate later approved Senate Resolution 56, which expanded the scope of the examination.

Over the course of the next two years, the augmented committee investigation received support from both Presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt, and bipartisan support from the Senate. On the committee itself, regardless of which party was in the majority and the pressures placed on the committee’s limited budget, committee members stood behind Mr. Pecora and worked to support his investigative efforts. Eventually, the inquiry became colloquially known as the Pecora Investigation.

Mr. Pecora acted first to obtain key documents from multiple financial institutions. Rather than request the documents and wait for them to be delivered, he preferred to walk directly into a bank and hand-deliver a subpoena. He and his staff then waited for the documents to be compiled and produced on the spot, and the team worked through the night copying relevant records and examining the financial information.

Mr. Pecora then designed and led hearings that dominated the news. The committee called wealthy, powerful bankers and corporate executives whom no one else had held accountable for their actions. Insiders explained that he scheduled hearings only when the committee’s research had uncovered important facts and incriminating records. Due to his detailed grasp of the documents, issues, and events and his strong interrogation skills, the committee often permitted Mr. Pecora to lead the questioning of witnesses. Hearing witnesses included:

- J.P. Morgan Jr., the most powerful financier of the time;

- Charles E. Mitchell, Chairman of National City Bank, then the largest U.S. bank;

- Richard Whitney, President of the New York Stock Exchange;

- Otto Kahn, senior partner at Kuhn, Loeb & Company, a wealthy investment bank;

- Albert H. Wiggin, former Chairman of Chase National Bank;

- Harry Sinclair, founder of Sinclair Oil;

- Jesse H. James, Chief of Reconstruction Finance Corporation; and

- John J. Raskob, former Vice President of Finance at DuPont and General Motors, and Chairman of the Democratic National Committee

The investigation unearthed a host of Wall Street abuses, including unethical tax practices, insiders given investment advantages not available to the public, investors misled about substandard securities, the short selling of stocks, “pooling” techniques to manipulate stock prices, the underwriting and sale of shaky securities, interest-free bank loans to insiders and favored clients, and more. The highly publicized hearings led to shattered reputations, resignations, firings, and even jail sentences. It also helped educate the American public about the nation’s financial institutions and how they’d contributed to the Great Depression.

In Congress, the Pecora Investigation laid the factual foundation for dramatic reforms to rein in unfair, unethical, or reckless financial practices and strengthen public protections.

- Glass-Steagall Banking Act of 1933: Passed by the Senate while J.P. Morgan Jr. was testifying, this law separated commercial banks from investment banks to prevent the diversion of deposits into risky investments, prohibited banks from trading on their own account instead of on behalf of customers, and created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to guarantee repayment of deposits if a bank were to fail.

- Securities Act of 1933: This law required issuers of stock to register new securities with the government and provide the public with information needed to make informed investment decisions. The law also established civil and criminal penalties for selling unregistered securities or providing inadequate or misleading stock disclosures.

- Securities Exchange Act of 1934: This law established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to protect investors and police financial markets, including by ensuring fair securities trading on exchanges like the New York Stock Exchange. It also established the system requiring securities issuers to file a variety of public reports with the SEC about their operations, financial condition, and investors.

These and other bills to limit abusive financial practices and safeguard investors and depositors were enacted with bipartisan support in Congress and with widespread support from the public.

“At a time of considerable questioning of the capitalist system, the hearings personalized the causes of the Depression. By producing a string of villains, they translated complicated economic problems into moral terms. Bankers, Pecora demonstrated, had abandoned their fiduciary responsibilities.”

Congress Investigates, p. 502

The Pecora Investigation proved once more, at a difficult time in the nation’s history, that Congress could investigate a complex subject and enact needed reforms. It created precedent for using congressional subpoenas to advance an investigation, compelling even the wealthy and powerful to comply with congressional information requests, and using congressional hearings to expose wrongdoing and educate the public. This investigation is also unique in celebrating the critical role that congressional staff play in oversight investigations. Ferdinand Pecora later served briefly as an SEC commissioner, before taking a seat on New York’s Supreme Court.

Learn More

- Committee on Banking and Currency investigation of Stock Exchange Practices: Complete transcripts of hearings, exhibits, and final report

- Federal Reserve History: Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall)

- Ferdinand Pecora: The Hellhound of Wallstreet

- The Man Who Busted the ‘Banksters’

- Senate.gov: Subcommittee on Senate Resolutions 84 and 234

- When Washington Took On Wall Street

Resources for Teachers

- Learning by Hearings lesson plan: Ferdinand Pecora and the 1929 Stock Market Crash

- Learning by Hearings snapshot summary