Portraits in Oversight:

Harry Truman and the Investigation of

Waste, Fraud, & Abuse in World War II

Harry S. Truman, though best known as the 33rd President of the United States, gained initial prominence in national politics as a Missouri senator from 1935 to 1945. His fame arose from his oversight efforts related to World War II.

As America’s involvement in the war seemed increasingly imminent and Congress allocated $10.5 billion to strengthen U.S. military bases and equipment, then-Senator Truman embarked on a 10,000-mile drive to see for himself how the money was being spent. The waste and wartime profiteering he saw across the country shocked him. He described seeing construction materials in the snow, “getting ruined. And there were men, hundreds of men, just standing around collecting their pay, doing nothing.”

Upon his return to Washington, he proposed establishing a special committee to investigate the state of the country’s defense contracts. On March 1, 1941, the Senate unanimously approved creation of the committee, directing it to investigate “the procurement and construction of supplies, materials, munitions, vehicles, aircraft, vessels, plants, camps, and other articles and facilities in connection with the national defense” (Senate Resolution 71). In May 1942, the committee was officially renamed the Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, but it became known as the “Truman Committee.”

As committee chair, Senator Truman resisted pressure from President Franklin D. Roosevelt to stack the committee with New Deal Democrats, choosing instead to build a bipartisan team of men he considered to be practical and honest, regardless of party affiliation.[1] Seven members were appointed to the committee upon its creation: Democratic Senators Truman, Thomas Connally of Texas, Carl Hayden of Arizona, James Mead of New York, and Monrad Wallgren of Iowa, and Republican Senators Joseph Ball of Minnesota and Ralph Owen Brewster of Maine. Three more members, Democrats Clyde Herring of Iowa and Harley Kilgore of West Virginia and Republican Harold Burton of Ohio, were added in October of that year, and Senator Hayden was replaced by Democrat Carl Hatch of New Mexico.[2]

From the beginning, Senator Truman insisted upon taking a fact-based approach to the committee’s work. “There is no substitute for facts,” Senator Truman often repeated in committee meetings. He also insisted that, working on behalf of the American people, the committee would act as a “benevolent policeman,”[3] guarding against wartime abuses. In a March 24, 1941 national address on NBC radio, he explained:

“This committee is a bipartisan one and has adopted a policy of making a thorough inquiry of the subjects it undertakes to investigate without prejudice or bias. There will be no attempt to muckrake the defense program, neither will the unsavory things be avoided. The welfare of the whole country is at stake in the successful conclusion of our national defense policy. Where there has been so much haste in the expenditure of such enormous sums there are bound to be leaks and mistakes of judgment. Many people believe in both patriotism and profits, but sometimes, unfortunately, profits come first with them. My experience with the public contractors is that they must be carefully checked on Government construction.”

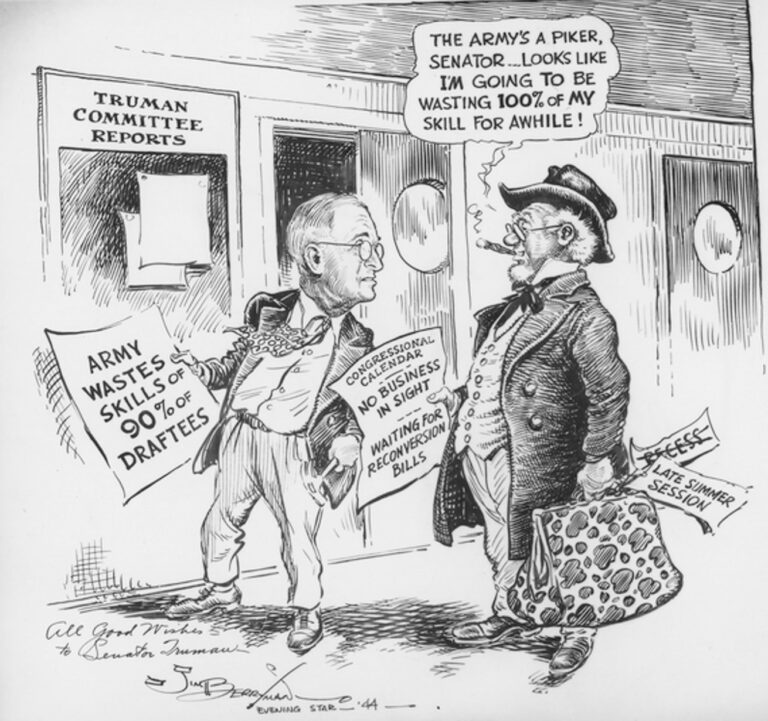

With an initial $15,000 budget, Senator Truman appealed to the American public on CBS Radio, asking that they write to the committee if they saw defense-related waste in their communities. The committee routinely read the citizen letters sent in and often used them as starting points in its investigations. Hitting the ground running, the committee quickly homed in on excessive spending by contractors hired for military housing projects. Its recommendation — that these types of projects be managed by the Army Corps of Engineers — saved the government an estimated $250 million. The early successes of the committee led to an increase in its budget to $50,000 by the fall of 1941.

Other findings by the committee included:

- The Carnegie-Illinois Steel Corporation sold faulty slabs of steel to be used in shipbuilding and falsified quality control reports;

- Defective engines made by the Curtiss-Wright Company and used in airplanes led to the death of student pilots;

- Standard Oil Company and Alcoa, which had exclusive patents or monopolies on critical war materials, had intentionally slowed the development of substitutes or created artificial shortages; and

- The Remington Company, according to Senator Truman, got “$600,000 for acting as advisors to the Government” but in his words: “[n]o one knows what this advice is or what it is worth.”

Some of the committee’s findings led to government lawsuits to recover damages for substandard equipment. For example, the War Department sued the Curtiss-Wright Company subsidiary Wright Aeronautical Corporation for damages related to faulty aircraft engines and named ten company executives as having conspired to defraud the government.[4] A committee staffer later disclosed that a letter from a concerned citizen alleging that the company was falsifying inspection records sparked the investigation.[5]

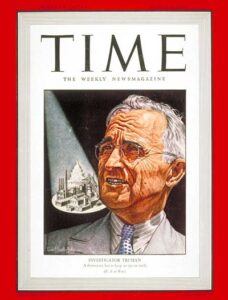

The Truman Committee not only uncovered substantial misuse of government funds but helped to build the public’s trust in Congress. Senator Truman made clear to his colleagues that they were not to seek publicity for their investigative work, but the committee still attracted attention from the mainstream media. In March 1943, Time Magazine featured “Investigator Truman” on its cover, which considerably raised his political profile. The accompanying article quoted one “Washingtonian” as saying, “There’s only one thing that worries me more than the present state of the war effort. That’s to think what it would be like by now without Truman.”

Spending less than $1 million on its investigations over seven years, it is believed that the Truman Committee:

- Saved the government $10 – 15 billion;

- Saved thousands of lives by uncovering defective equipment and materials that were to be used by troops, and unsafe conditions at plants where wartime materials were being manufactured; and

- Shortened WWII by streamlining federal contracting practices.[6]

The hard-working, bipartisan culture of the Truman Committee cannot be overstated. All 432 public hearings were open to attendance by all senators, and the nearly 1,800 witnesses called to testify were treated with respect. The committee held an additional 300 executive sessions, and committee members took hundreds of field trips to investigate the war effort directly. Most impressively, of the 51 reports released by the committee over its seven years, all were approved unanimously. Members met in Senator Truman’s office to discuss each report point-by-point, resolving every difference before leaving the office. The members built strong relationships with one another, and later President Truman appointed Democratic Senator Wallgren to the Federal Power Commission and Republican Senator Burton to the Supreme Court.[7]

In 1944, Senator Truman stepped down as committee chair to focus on the presidential election – he had been chosen as President Roosevelt’s vice-presidential candidate largely because of his oversight work. The Truman Committee continued operations, however, until 1948, chaired by both Democrats and Republicans. Following the war, the committee performed an in-depth analysis of the WWII national defense programs and made recommendations for future efforts. Its final report was issued on April 28, 1948.

The records of the Truman Committee, which are held by the National Archives, total 775-feet when stacked together. They touch on almost every aspect of the war effort, with archival categories that include the following:

“Manpower issues, such as training programs, military personnel, labor organizations, and the so-called ‘dollar-a-year men’ … ships and shipbuilding, military establishments and facilities, shortages of material, reserve supplies of strategic and other materials, transportation, contracts and procurement, conversion and reconversion … food, housing, racial discrimination, war films, disposal of surplus property, war profiteering, lobbying of Government agencies by private enterprise, and specific charges of fraud and corruption … treatment of prisoners of war and the military government in Germany … Federal agencies, most notably the War Department, Navy, U.S. Maritime Commission, and War Production Board.”[8]

Recognizing the Truman Committee’s valuable contribution to the country, in 1948, the Senate Committee on Expenditures in the Executive Departments created the Subcommittee on Investigations to emulate the Truman Committee’s fact-based, bipartisan approach to investigations.[9] The new subcommittee was given custody of the Truman Committee files and records. Around 1952, it was renamed the “Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations” to distinguish it from the temporary bodies formed by Congress to conduct a particular investigation and then dissolve. “PSI” remains active in the Senate today, the only Senate subcommittee that is devoted solely to complex oversight investigations and functions with no legislative responsibilities.[10]

In a 1968 interview, Wilbur Sparks who served as a lawyer on the Truman Committee offered this assessment of its oversight work: “History may very well show that never before or since has there been a congressional committee which conducted itself in such a nonpartisan manner.”

[1] Yenne, B. (2021). The Complete Book of US Presidents, Fourth Edition. Crestline Books.

[2] Official congressional directory for the use of the United States Congress, 77th Cong. (1942), https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015022759099.

[3] United States Senate. (n.d.). Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program. https://www.senate.gov/about/powers-procedures/investigations/truman.htm.

[4] The Daily Herald. (2013, July 11). Army officers are removed by Truman probe. Herald of Yesterday: July 12, 1943. https://www.columbiadailyherald.com/article/20130711/NEWS/307119905.

[5] Hess, J. N. (1968, September 5 and 19). Oral history interview with Wilbur D. Sparks, at 67-68. Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/oral-histories/sparkswd.

[6] Poole, R. M. (2012, August). How Truman led the charge in Congressional oversight. HistoryNet. https://www.historynet.com/when-everybody-loved-congress-2.htm.

[7] Hess, J. N. (1967, November 28). Matthew J. Connelly oral history interview, November 28, 1967. Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/oral-histories/connly1.

[8] National Archives. (2016, August 15). Guide to Senate records: Chapter 18 1921 – 1946. https://www.archives.gov/legislative/guide/senate/chapter-18-1921-1946.html#18D-11.

[9] Senate Oral History of Ruth Young Watt, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/oral_history/Ruth_Young_Watt.htm.

[10] Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations historical background. (n.d.) Homeland Security & Government Affairs Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Retrieved September 30, 2021, from https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/PSIHistoricalBackgroundto115th.pdf.

Learn More

- Constitutional Accountability Center: The Truman Committee and the Importance of Emergency Oversight

- Fighting Waste: The Truman Committee 1941 – 1944

- How Truman Led the Charge in Congressional Oversight

- Keeping Watch on the Home Front

- The Watchdog: How the Truman Committee Battled Corruption and Helped Win World War Two by Steve Drummond