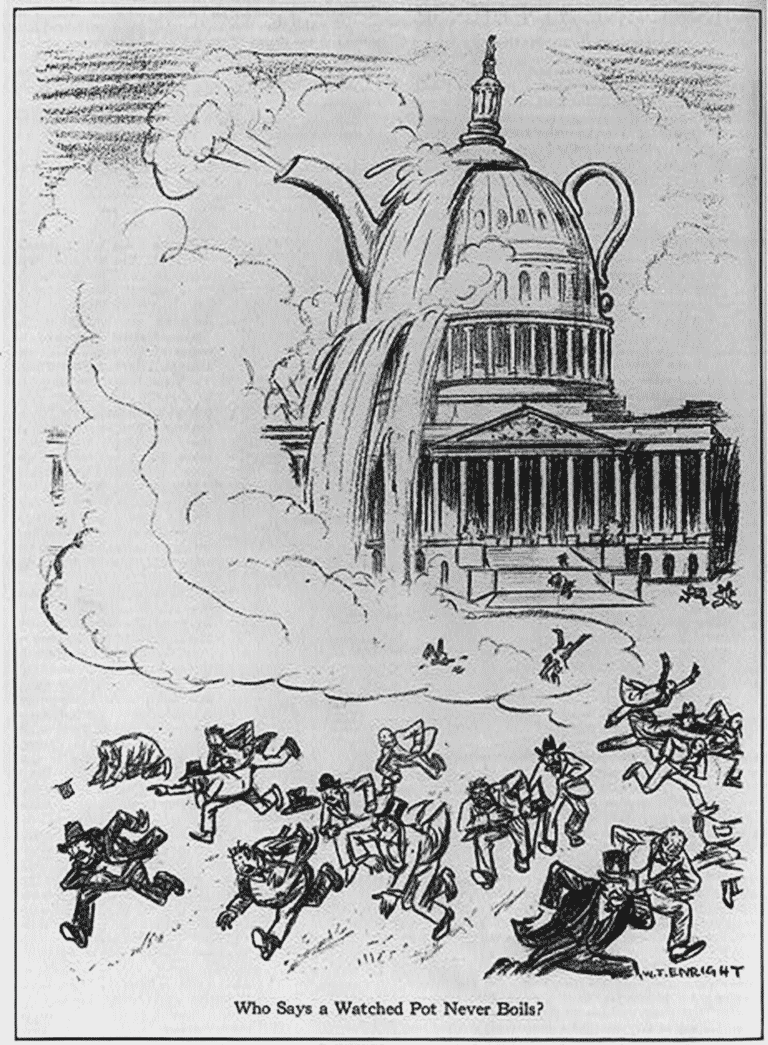

Portraits in Oversight:

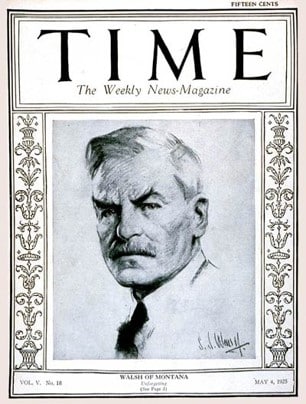

Thomas Walsh

and the Teapot Dome Investigation

Thomas Walsh represented the state of Montana in the U.S. Senate from 1913 to 1933. During his tenure, he played a critical role in one of the most important Senate investigations into federal bribery, corruption, and a failure to prosecute, as well as the right of Congress to investigate and expose wrongdoing. Known as the Teapot Dome scandal, the inquiry not only exposed one of the worst government scandals in American history, but also helped change the legal landscape of congressional investigations forever.

In 1920, President Woodrow Wilson set aside three tracts of oil-rich land to be used in national emergencies. The oil fields were located in Elk Hills and Buena Vista, California, and Teapot Dome, Wyoming. President Wilson transferred control of the oil fields from the Secretary of the Interior to the Secretary of the Navy, who catalogued them as Naval Oil Reserves Number One, Two, and Three.

Under the following administration of President Warren G. Harding, however, Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall advised the President to return control of the land to his department following a conversation he had with Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby. On May 21, 1921, President Harding signed Executive Order 3474, transferring control of the Naval Oil Reserves from the Secretary of the Navy to the Secretary of the Interior.

The oil fields came to the attention of Congress in April 1922. Senator John Kendrick, a Democrat from Wyoming, had received a flurry of correspondence from constituents informing him of backroom deals that had resulted in the private leasing of the Teapot Dome land tract to Mammoth Oil Company, owned by oil tycoon Harry F. Sinclair. Earlier, the Elk Hills tract had been leased to Edward L. Doheny, owner of Pan American Petroleum and Transport Company. Both leases provided terms very favorable to the oil companies, and the Teapot Dome lease was made with no competitive bidding. Neither the public nor Congress had been informed of the leases beforehand, and a request for more information by Senator Kendrick was initially denied by the Interior Department.

Senator Robert La Follette, a Wisconsin Republican who had been approached by concerned conservationists, introduced resolutions on April 21 and 28, calling on the Senate Committee on Public Land and Surveys to investigate the oil leases. Senator La Follette also urged Senator Thomas Walsh, the committee’s most junior minority member, to head up the investigation which was expected to be both tedious and unfruitful. Some senators were also wary of questioning Secretary Fall, who had been their colleague representing New Mexico in the Senate before his Cabinet appointment. The committee’s Republican majority planned to focus its attention on other issues. It took time, but what became known as the Walsh Committee investigation eventually uncovered facts that grabbed the attention of the American public, exposed widespread wrongdoing, and shattered multiple government and private sector careers.

Senator Walsh began the investigation by combing through 6,000 pages of documents sent by the Interior Department, accompanied by a letter from President Harding stating that he was aware of the leases beforehand and had approved them. During this time, Senator La Follette’s offices were mysteriously broken into and ransacked, and Senator Walsh expressed the belief that his phone was tapped. In early 1923, Secretary Fall left President Harding’s cabinet and accepted a job with Harry Sinclair, sparking further suspicion as rumors circulated about his newfound wealth.

On August 2, 1923, President Harding died unexpectedly, and Calvin Coolidge assumed the presidency. The first Senate hearing on the Teapot Dome scandal was held on October 24, with Albert Fall as its first witness. He defended the private oil leases, explaining that the move was intended to ready the country for possible war with Japan. Navy Secretary Denby testified next, confirming Mr. Fall’s account. In the following months, Senator Walsh received information about Mr. Fall’s unexplained new wealth in the wake of the leases, including improvements to his New Mexico ranch and other land deals. Senator Walsh secured testimony from Albuquerque newspaper editor Carl Magee who said the upgrades to the Fall property were significant: “The conditions were so changed I couldn’t recognize it.” That same day, the Fall ranch manager told the committee that Harry Sinclair had visited Mr. Fall in December 1921, and gifted him with substantial livestock.

Revelations regarding Mr. Fall’s finances continued to unfold as more witnesses came forward, and public interest in the investigation skyrocketed. Edward McLean, owner of the Washington Post, revealed that he had loaned Mr. Fall $100,000.00 in 1921, but that the check had been returned, uncashed. Mr. Fall refused to answer questions about this event, other than to say in a letter that he had returned the check, “because I found other sources.” He further expressed doubt that Senator Walsh had the authority to question his financial dealings, stating, “[T]hat is my own private affair. I do not feel called upon to discuss it either with Senator Walsh or any other man.” Edward Doheny, whose company leased the Elk Hills tract, later revealed in Senate testimony that he’d loaned Mr. Fall $100,000 in cash, while insisting the loan had nothing to do with the oil lease. Federal prosecutors would later indict Mr. Fall for taking a $100,000 bribe.

On January 26, 1924, Senator Walsh met with the Public Lands Committee and announced his intention to introduce resolutions requesting President Coolidge to annul the private leases as illegally granted and appoint special counsel to investigate those involved. The committee agreed unanimously to support the resolutions. Before he could bring them to the Senate floor, however, President Coolidge announced that he had decided on his own to employ special counsel to investigate the two leases “so that if there is any guilt; if there is civil liability it will be enforced; if there is any fraud it will be revealed; and if there are any contracts which are illegal they will be canceled.”[1]

The media storm following the two announcements demonstrated the gravity of the Walsh Committee’s findings. Overall Senate support for the Teapot Dome investigation remained strong and bipartisan, despite occasional accusations of partisanship. For example, on January 23, 1924, Senator Irvine Lenroot – then chair of the Public Lands Committee – told his colleagues, “The committee, without regard to party lines, all the members of the committee, are cooperating and endeavoring to get to the truth regarding this matter.” On January 31, 1924, when Senator Walsh brought two resolutions to the Senate floor to require the oil leases to be investigated by special counsel, they passed unanimously. They also passed the House on a bipartisan basis.

While President Coolidge considered candidates for the special counsel positions, the Walsh Committee hearings continued. Senator Walsh called Mr. Fall to testify again, but he refused to appear. He claimed he was ill, but also asserted that the committee had no authority to question him, because the Senate resolution authorizing the investigation in the previous session of Congress had expired. Additionally, he stated that the most recent resolutions meant that only President Coolidge had the authority to investigate the oil leases. To avoid any further questions, he invoked his Fifth Amendment right to remain silent.

President Coolidge nominated former Democratic Senator Atlee Pomerene of Ohio and Owen Roberts, a Republican attorney practicing in Philadelphia, as a bipartisan team of special counsel to conduct the oil lease investigations. When President Coolidge met with Mr. Roberts for the first time in the Oval Office, he reportedly told him, “If you are confirmed, there is one thing you must bear in mind. You will be working for the government of the United States – not for the Republican Party, and not for me. Let this fact guide you, no matter what ugly matters come to light.”[2] Both nominees were confirmed by the Senate on February 16, 1924; Secretary Denby resigned the same day.

The Walsh Committee hearings pressed on, taking testimony from Washington Post owner Edward McLean, Republican Governor of Pennsylvania Gifford Pinchot, Republican Governor-General of the Philippines Leonard Wood, Republican National Chairman Will Hays, and others. The evidence revealed that Mr. Sinclair had loaned the Republican Party $75,000 just prior to the 1920 Republican convention, which some witnesses claimed was for the purpose of securing private oil leases from whomever prevailed in office. Mr. Sinclair refused to answer questions during a March 23rd hearing, asserting ten times that only the courts, not the Senate, had the jurisdiction to question him on private matters. On March 24, the Senate voted to hold him in contempt, and he was indicted by a grand jury on March 31, 1924. He was eventually sentenced to three months in prison for contempt of Congress.

Before the release of the committee’s final report, Senator Walsh made an appearance on the radio and wrote a column in Forum Magazine to address rumors that the investigation was overly partisan. He explained that the committee was working in a bipartisan manner, and many of the accusations of partisanship came from people under investigation and seeking to divert attention from their own misconduct. On WRC radio, he stated:

If, upon a crucial question arising in the course of the hearings, action was taken the propriety of which can be questioned, some Republican member or members, if not all such, must have voted with their Democratic associates, moved by a desire to develop the actual facts, notwithstanding the disclosures might be to some extent to the disadvantage of their party…. Except in a few instances and in relation to matters of relatively inferior importance all testimony taken by the committee with which I have been serving was received, and every proceeding entered upon was taken, without objection.

In two years of investigation, the Walsh Committee held 84 days of hearings with 144 witnesses. Tens of thousands of documents were examined, many by Senator Walsh alone prior to the first hearing. Transcripts of the hearings and correspondence between witnesses published by the U.S. Government Printing Office span three volumes and 3,600 pages. The bipartisan majority report was released on June 6, 1924.

The Teapot Dome investigation led to senior government personnel leaving office, cancellation of the oil leases, and several civil cases and criminal convictions:

- United States v. Albert B. Fall: Mr. Fall was convicted of accepting a $100,000 bribe from oil magnate Edward Doheny. The court imposed a $100,000 fine and a one-year prison sentence. He was the first cabinet member in American history to be convicted of committing a crime while in office.

- United States v. Albert B. Fall and Harry F. Sinclair: The trial of Mr. Fall and Mr. Sinclair on charges of conspiracy to defraud the United States ended in a mistrial when it was discovered that Mr. Sinclair had jury members followed by private detectives. Mr. Sinclair was later found guilty of criminal contempt of court and jury tampering and, in addition to the three-month sentence he’d received for contempt of Congress, he was sentenced to six months in prison.

- United States v. Pan American Petroleum and Transport Company and United States v. Mammoth Oil Company: These two civil cases resulted in cancellation of the oil leases.

The investigation also produced a key congressional oversight law. When the Walsh Committee sought to review tax returns filed by major figures in the Teapot Dome scandal, it was forced to ask President Coolidge for copies, because a 1910 law had given the president sole authority to disclose federal tax returns. To empower Congress to investigate tax issues without seeking the president’s permission, in 1924, Congress enacted a law stating that if the chair of the House Committee on Ways and Means, Senate Committee on Finance, or Joint Committee on Taxation requested a tax return or return information, the Treasury Secretary “shall furnish” it. Now codified at 26 U.S.C. 6103(f)(1), Congress has used the authority only sparingly since 1924, but it has remained an important oversight tool.

Perhaps even more importantly than the legal actions and new law, the Walsh Committee sparked a second Senate investigation of the Justice Department, leading to litigation before the Supreme Court which, for the first time, clearly upheld Congress’ right to investigate and compel information. After Mr. Pomerene and Mr. Roberts were confirmed as special counsel and began their investigation, Mr. Roberts met with Senator Walsh and warned him, “I wouldn’t depend on the Justice Department for investigative purposes, nor would I approach the Attorney General’s office for information if I were you …. It is my conviction that the man would go to any lengths to protect himself and his friends – and make no mistake about it, the people we are after are friends of the Attorney General.”[3]

Troubled that Attorney General Harry Daugherty may have deliberately failed to investigate and prosecute those implicated in the Teapot Dome scandal, Senator Burton Wheeler of Montana introduced Senate Resolution 157, creating the Select Committee on Investigation of the Attorney General. Adopted on February 29, 1924, the committee was chaired by Republican Smith W. Brookhart of Iowa and also included Democratic Senator Wheeler, Democratic Senator Henry Ashurst of Arizona, Republican George Moses of New Hampshire, and Republican Wesley Jones of Washington.

The select committee held multiple hearings in March and April of 1924. Twice, subpoenas were issued for the Attorney General’s brother, Mally S. Daugherty, to appear before the Senate – he was president of Midland National Bank which was believed to have been involved in the scandal. President Coolidge, who had initially resisted calls to fire Attorney General Daugherty, finally demanded his resignation on March 28, 1924. Suspicions regarding his brother only increased when he failed to respond to either Senate subpoena or to appear before the committee.

Senate President Pro Tempore Albert B. Cummins issued a warrant for Mally Daugherty’s arrest, and a deputy sergeant at arms took him into custody. He responded by filing a writ of habeas corpus in federal court, arguing that the Senate had no right to hold or question him. A lower court granted the writ to free him, but the Supreme Court reversed the decision in the seminal 1927 case, McGrain v. Daugherty. That Supreme Court decision explicitly recognized the right of Congress to investigate, issue subpoenas, and compel information, including the right to enforce its subpoenas through imprisonment. The Supreme Court stated:

“We are of opinion that the power of inquiry—with process to enforce it—is an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative function…. A legislative body cannot legislate wisely or effectively in the absence of information respecting the conditions which the legislation is intended to affect or change, and where the legislative body does not itself possess the requisite information — which not infrequently is true — recourse must be had to others who do possess it. Experience has taught that mere requests for such information often are unavailing, and also that information which is volunteered is not always accurate or complete, so some means of compulsion are essential to obtain what is needed.”

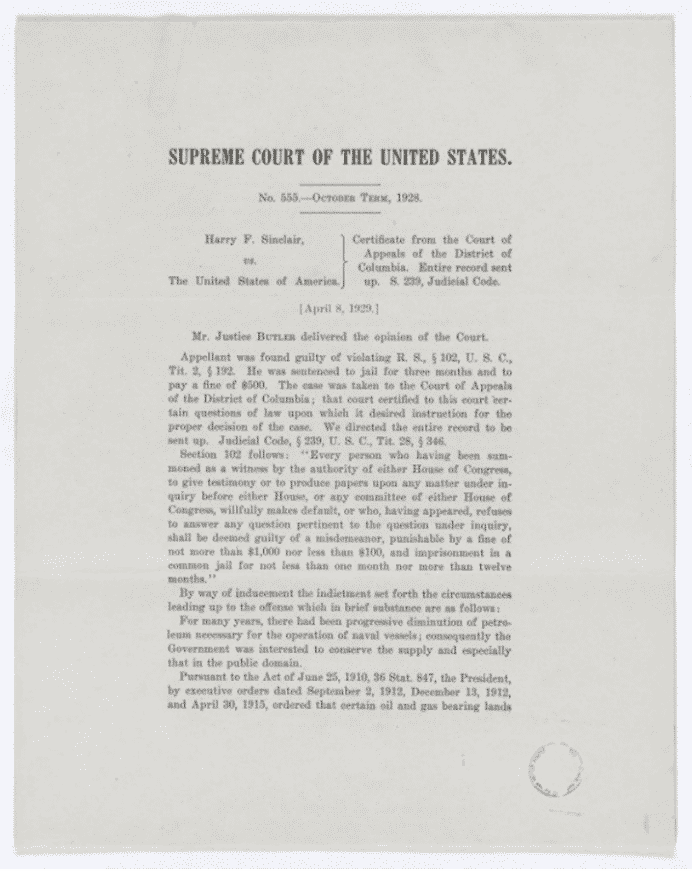

In a separate case, the Supreme Court also upheld Harry Sinclair’s contempt of Congress conviction for refusing to answer questions posed by the Senate committee. Specifically, the 1929 decision upheld the following law:

“Every person who having been summoned as a witness by the authority of either House of Congress, to give testimony or to produce papers, upon any matter under inquiry before either House, or any committee of either House of Congress, willfully makes default, or who, having appeared, refuses to answer any question pertinent to the question under inquiry, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor.”

Senator Walsh’s persistence in reviewing the evidence, concentration on the facts, and bipartisan investigative approach uncovered government corruption that might otherwise have remained hidden, helped cleanup federal procurement practices, and led to the bedrock Supreme Court case recognizing the right of Congress to conduct oversight.

Learn More

- Congress Investigates: A Critical and Documentary History, Volume 1, Chapter 13 by the Robert C. Byrd Center

- Investigation of Hon. Harry M. Daugherty, Formerly Attorney General of the United States: Hearings Before the Select Committee on Investigation of the Attorney General (Volume 1) (Volume 2) (Volume 3)

- Senate Investigates “Teapot Dome” Scandal

- “The True History of Teapot Dome” by Senator Thomas J. Walsh, Forum, July 1924 (Proquest subscription required)

- United States v. Albert B. Fall: The Teapot Dome Scandal by Jake Kobrick