Portraits in Oversight:

Congress and the Love Canal Disaster

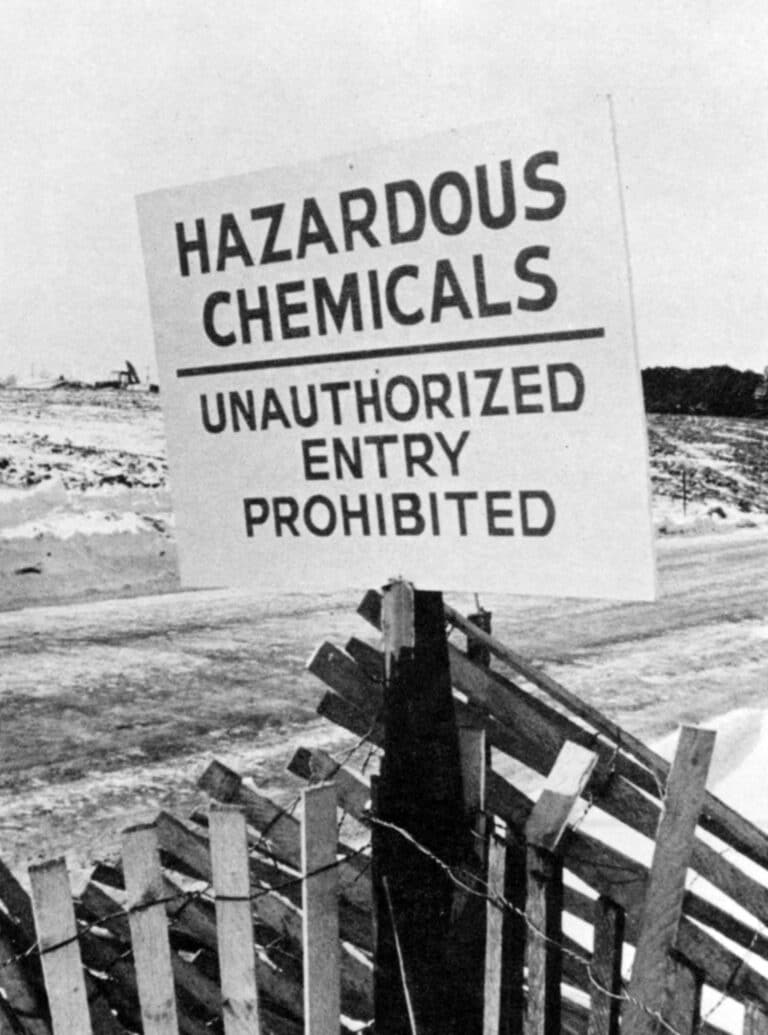

Love Canal, an abandoned canal project in Niagara Falls, New York, became a dumping site for Hooker Chemical Company’s industrial waste from 1942 to 1953. Over the next 20 years, the poorly contained toxic chemicals leached into the soil and water of the surrounding neighborhoods, causing severe health problems including respiratory issues, cancers, blood diseases, miscarriages, and still births. In 1979, multiple congressional oversight investigations exposed the deadly impact of that environmental disaster, disclosed that it was just one of thousands of hazardous waste sites across the country, and led to enactment of what is now known as the Superfund Program to identify and begin to clean up those toxic sites.

In 1894, William T. Love began excavating the Love Canal to create a cheap source of hydrolytic power for his envisioned “model city.” He abandoned the project in the early 1900s, after digging a canal only 3,000 feet long and 100 feet wide. It was used as a swimming hole by the locals until it was purchased by the Hooker Chemical Company in 1942. Over the years, a neighborhood of over 800 homes was built near the canal.[1] During the same period, Hooker Chemical buried 21,800 tons of toxic chemicals in the canal, topping the landfill with clay before selling the site to the local school board in 1953, for $1, with a disclaimer in the deed releasing it from any responsibility for damages caused by the buried chemicals. The board reserved land for a school on the site and sold the remaining property for a park and residential development. In 1955, two elementary schools opened on the land.[2] In 1958, the Niagara Falls Health Department saw the first signs of trouble when children experienced chemical burns from exposed waste on the site, but it took no action.[3]

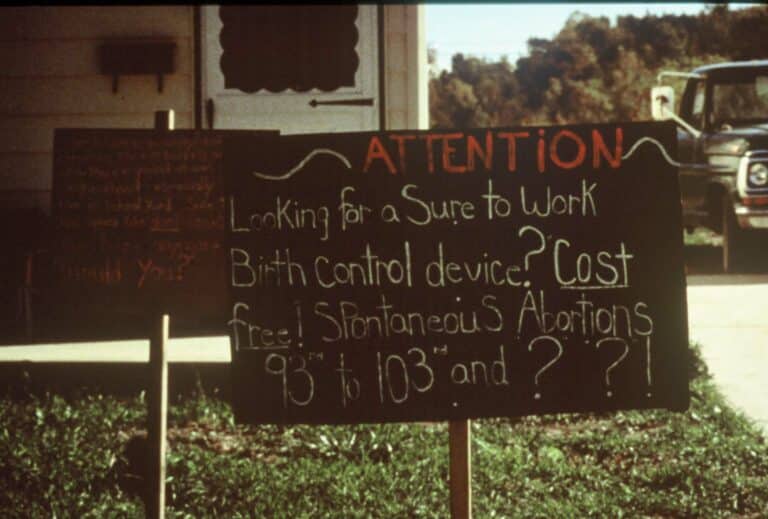

Twenty years later, in the summer of 1976, after three years of heavy rain and snow, community members began complaining about chemical waste pooling in their backyards and basements, as well as noxious odors in their homes. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) — established just six years earlier in 1970 — the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, and the New York State Department of Health tested water, air, and soil samples near the Love Canal landfill in 1977 and 1978. They found 82 chemical compounds, at least 11 of which were carcinogens such as benzene and dioxin.[4]

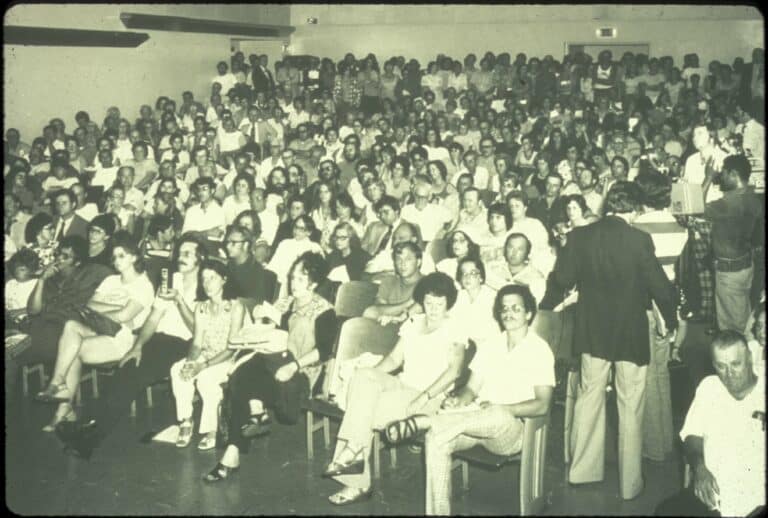

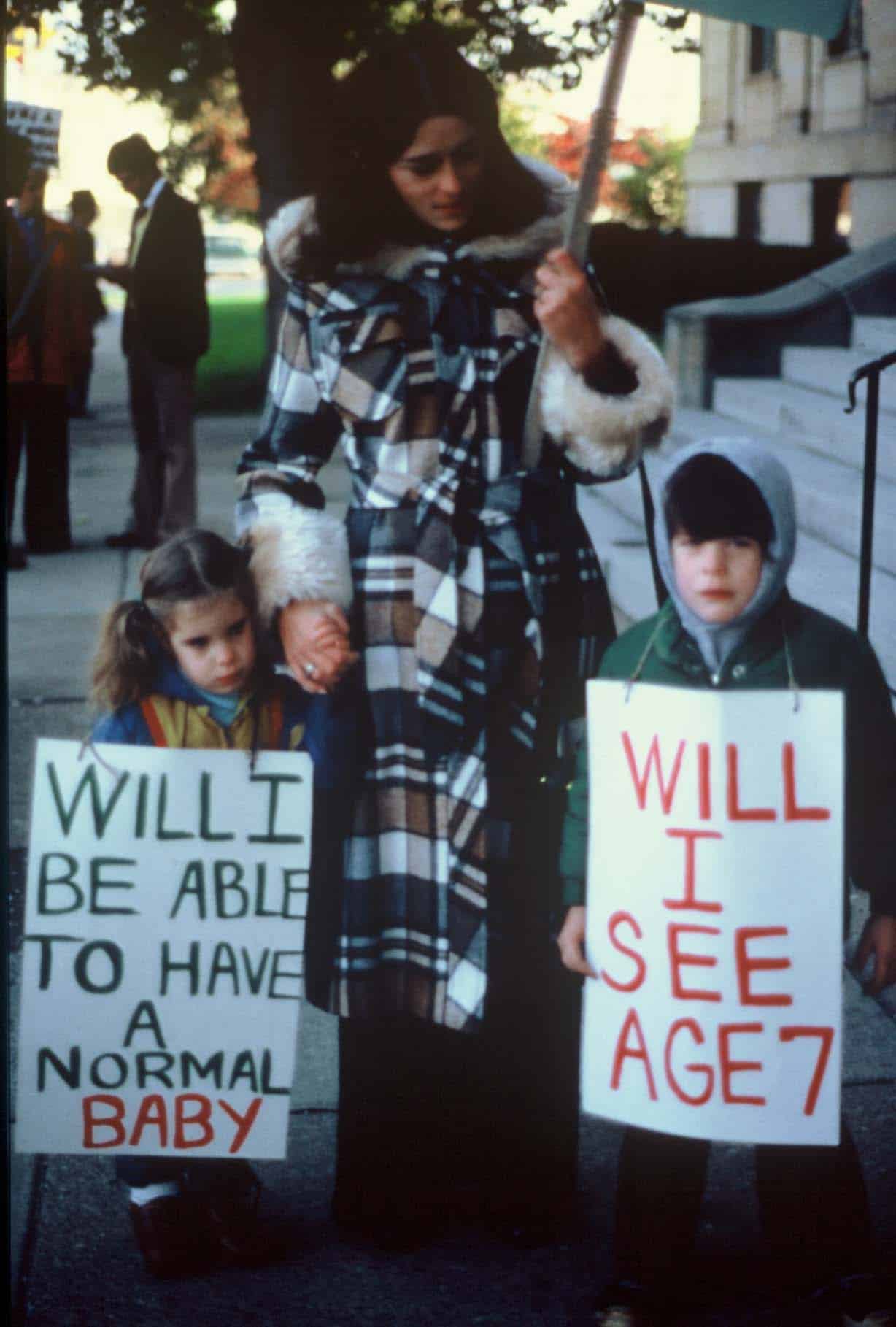

In August 1978, resident Lois Gibbs organized the Love Canal Homeowners Association (LCHA). Her son Michael had started experiencing health issues shortly after they moved to the neighborhood, including asthma, pneumonia, urinary tract disorder, and seizure disorder. Her daughter, three years younger than Michael, had been diagnosed with a rare blood disease. Doctors did not identify a cause for either ailment, but Ms. Gibbs believed toxins from Love Canal were responsible.[5] Several hundred families joined the LCHA within 48 hours of its inception, and it eventually represented more than 90% of the area’s residents.

On August 2, 1978, New York State Health Commissioner Robert Whalen declared a state of emergency in the neighborhood and ordered the evacuation of pregnant women and children under two. On August 7, 1978, President Jimmy Carter declared the first federal state of emergency stemming from a man-made environmental disaster. The emergency declaration provided federal funding for remediation efforts and relocation costs for 239 families living in the two rings of homes closest to the landfill.[6] The state of New York purchased more than 200 homes for almost $7 million.[7] At the same time, at least 700 families did not qualify for the 1978 relocation, even though Health Department tests confirmed toxic substances were in their homes at dangerous levels. Most of the working-class residents could not afford to move without government aid.

In September 1978, New York issued a special report on the Love Canal disaster. It stated: “Described as an environmental time bomb gone off, Love Canal stands as a testimony to the ignorance, lack of vision and proper laws of decades past which allowed the indiscriminate disposal of such toxic materials.”[8] It found that women living in the Love Canal neighborhood were almost 1.5 times more likely than the average woman to have a miscarriage, and identified at least five children born with birth defects and developmental disabilities in the relatively tiny community.[9]

Love Canal also caught the attention of Congress. While multiple committees eventually held hearings on aspects of the tragedy, the first and most substantial series of hearings was held by the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, precursor to today’s Energy and Commerce Committee. The oversight subcommittee’s 13 public hearings, which took place from October 1978 to June 1979, heard from 106 witnesses, many of whom provided chilling details about the Love Canal site:

- Elliot Lynch, former chief chemist of the Niagara County Water District, testified that he witnessed Hooker Chemical trucks dumping waste directly into the canal, uncontained, only 60 feet from the county water treatment plant.

- Love Canal resident Lois Gibbs testified that her son’s school, with 400 students, was located over the canal. She recalled, “Drums have popped up right on the baseball diamond. … [T]hey would cover it up with clay and they would allow the children to go back there. … [R]ight now you have men out there with respirators on, rubber boots, and rubber gloves. Everything is contaminated. That is the same place my children played last summer.”[10]

- A Niagara Falls pediatrician asked: “Where do you go from a medical standpoint? I treat the children symptomatically with medications to help them breath better. … We have looked for [a cause,] and we cannot find them in these people. Yet they all have similar symptoms.”[11]

- A cancer research scientist testified that the evidence indicated the toxins were not confined to the canal but had leached through streambeds and swamps into other residential areas, and a minimum of 140 additional families and perhaps as many as 500, needed to be relocated immediately.[12]

- New York officials testified that because the Love Canal site did not, under existing law, meet the legal definition of a “disaster,” much of the federal assistance used for situations like floods and tornadoes was not available.[13]

- One New York official testified that his department was preparing a report identifying other toxic dump sites throughout the state, and the still growing list already included 500 sites.[14]

- When Hooker Chemical was grilled about its actions, the company noted that the deed selling Love Canal to the school board explicitly referenced the buried chemicals; the clay used to contain the waste was considered sufficient under the law at the time of the sale; and both parties to the sale had agreed to free the company from any liability associated with the chemicals in the landfill.

In addition to digging into the details of the Love Canal disaster, subcommittee chair Bob Eckhardt of Texas made clear that toxic waste problems were not confined to that one site, explaining that “nationwide approximately 90 billion pounds of toxic wastes are generated each year” and, of that amount, an estimated “90 percent of hazardous waste products are disposed of in a manner which may be detrimental to good health and the environment.”[15] He noted that, although Congress had passed the Resources Conservation and Recovery Act in 1976, that law did not address abandoned dump sites like Love Canal, and the federal government had no reliable estimates as to how many toxic industrial sites might exist across the country.[16]

To demonstrate the scope of the problem, the subcommittee took testimony about another Hooker Chemical waste site in New York near Hyde Park:

- Local union leaders testified that members working in plants near the Hyde Park landfill had disproportionately high incidences of “cancer; breathing and respiratory problems; skin rashes; lumps, growths, and cysts; blood diseases; heart problems; high blood pressure; and sinus.”[17]

- Hyde Park resident Fred Armagost testified about his respiratory problems and those of his children and grandchildren, while the parent of one-year old Susan Jasper described how her severe respiratory issues led to bouts of pneumonia and hospitalization.

- Then Senator Al Gore, Democrat of Tennessee, who had toured the Hyde Park area, described the strong chemical odors and black sludge that covered Bloody Run Creek.[18]

- The subcommittee’s ranking member Norman Lent, a New York Republican, questioned why the New York Health Department was working with Hooker Chemical to investigate the Hyde Park landfill. He noted that, not only did the agency allow Hooker to dig the wells being analyzed, but the agency also shared samples and data with the company, despite obvious conflicts of interest.[19]

The oversight subcommittee also investigated and took testimony about toxic waste sites in states other than New York:

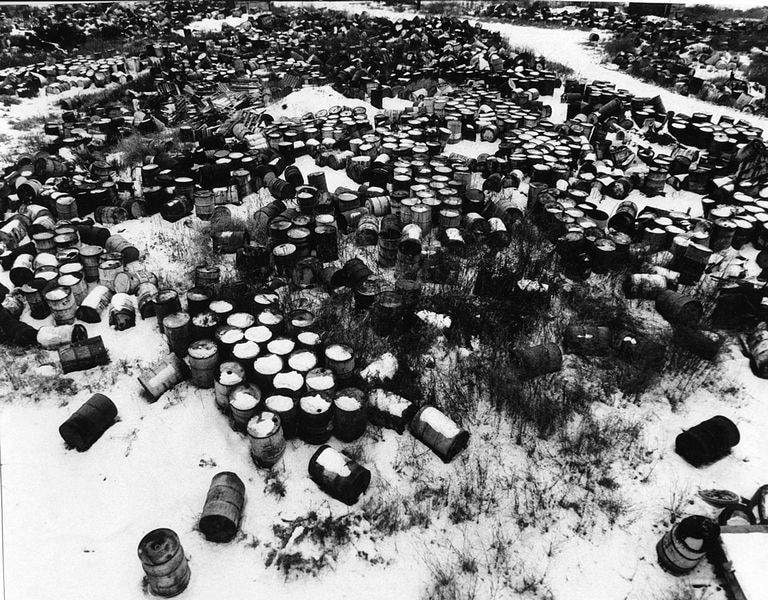

- Governor Julian Carroll of Kentucky described an environmental disaster caused by 100,000 drums of industrial waste on a 23-acre property near Louisville known as the “Valley of the Drums.”[20]

- Representatives from 14 states testified at various hearings about in-state toxic waste sites, and the subcommittee eventually “investigated specific waste disposal problems in Tennessee, Montana, Idaho, Florida and Louisiana.”[21]

- A subcommittee questionnaire sent to 53 large domestic chemical producers uncovered evidence of “several thousand” waste disposal sites.[22]

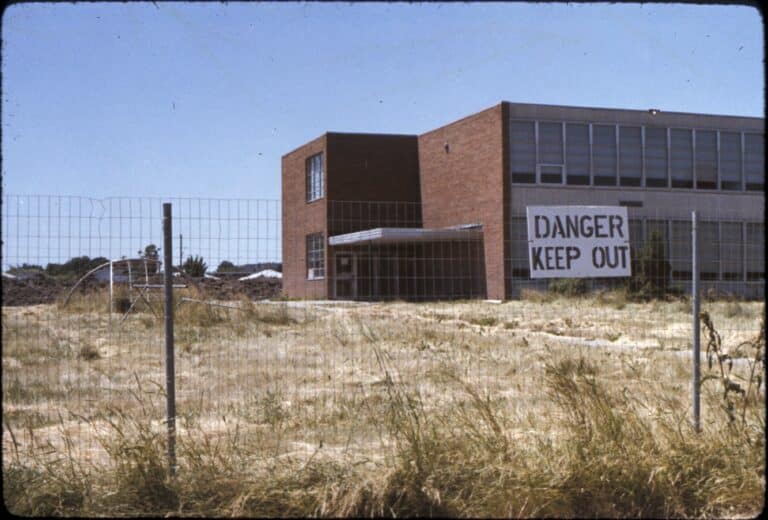

Tensions flared at one hearing on April 5, 1979, examining cleanup efforts at an illegal dump site at a factory owned by Chemical Control Corporation in Elizabeth, New Jersey. The company president and five other executives had been sent to prison and fined for the illegal disposal. An EPA administrative order directed the company to “initiate site cleanup to dispose of 1,200 drums per month and to clean up any spillage.”[23] However, Rep. Matt Rinaldo, the Republican member representing the New Jersey district where the factory was located, protested the lack of meaningful progress cleaning up the toxic waste:

The administrative order was issued, but nothing has actually happened. The fact of the matter is that to this day we don’t know what is under some of those drums. …[O]n Tuesday, the State police had to be called in to remove 125 pounds of explosive material – picric acid. … There is cyanide and potentially explosive materials in there. … Yet everybody is sitting around and doing nothing. So please don’t come here and tell me what a great job you are doing. You are not.[24]

At a hearing held on June 4, the General Accounting Office told the subcommittee that its analysis of 26 states’ enforcement and cleanup programs for hazardous waste found that only California and Texas had actually initiated any sort of programming.[25] In response, Republican Rep. Marc Marks of Pennsylvania observed: “You are saying that this country does not have a system to protect its citizens against hazardous waste.”[26]

At the same hearing, EPA administrator Douglas Costle explained that current law did not address problems associated with past hazardous waste sites, and EPA had only limited statutory authority and resources to address them. He testified that, nevertheless, hazardous waste sites had become the agency’s top enforcement priority; it had already assigned 100 employees to investigate potential sites; and the agency was considering lawsuits against companies responsible for 44 dump sites to recoup cleanup expenses.[27]

The subcommittee’s final hearing on June 19, 1979, took testimony from California officials who described a fertilizer plant in Lathrop, California, run by Occidental Chemical, a Hooker Chemical subsidiary.[28] Internal company documents obtained by the subcommittee showed that as early as 1975, Occidental had knowingly discharged “more than 10,000 tons of waste water containing … about 5 tons of pesticide per year” into the ground.[29] A memo to Occidental headquarters in Houston noted, “Should the water quality control regulatory agencies become aware of the fact that we percolate our pesticide wastes, they could justifiably close down our entire Ag Chem plant operation.”[30]

After the hearings concluded, the subcommittee produced a bipartisan report in September 1979, with findings and recommendations. Its key findings included that U.S. industrial sites contained “large quantities of hazardous waste,” “[u]nsafe design and disposal methods [were] widespread,” the environmental dangers were “substantial” and posed “major health hazards,” and the government response to the public health threats was “inadequate.”[31] Members on both sides of the aisle called for action, with subcommittee Republicans stating that combatting the “indiscriminate dumping” of toxic wastes should be a “priority.”[32]

Among other measures, the report called on EPA to promulgate regulations on hazardous waste disposal, create a complete inventory of all hazardous waste disposal sites in the country, compile a more comprehensive list of toxic substances, and conduct more comprehensive monitoring for leachate and groundwater contamination. The subcommittee also recommended enacting legislation to establish a cleanup program for abandoned waste sites, increase funding for cleanups, and strengthen criminal penalties for violations.[33]

While the House took the lead on the issue, the Senate also held hearings on hazardous waste disposal. In March 1979, for example, two joint hearings were held by two subcommittees of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee. The Subcommittee on Environmental Pollution was chaired by Sen. Edmund Muskie, Democrat from Maine and its ranking member was Robert Stafford, Republican from Vermont. The Subcommittee on Resource Protection was chaired by Sen. John Culver, Democrat from Iowa, and its ranking member was Howard Baker, Republican from Tennessee. Their joint hearings heard from some of the same witnesses as the House oversight subcommittee, including representatives of EPA, state agencies, Hooker Chemical, the Love Canal Homeowners Association, and the scientific community.

“The full legacies of this problem for future generations will not be realized for years, but there must be a commitment now to set into motion efforts to deal effectively with what we know exists today, to cleanup those problems that are due to past improper practices, and to prevent as much as possible the occurrence of more such problems in the future.”

Dr. Glenn Paulson, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection

In addition, the Senate Subcommittee on Oversight of Government Management, part of the Committee on Governmental Affairs, held hearings in the summer of 1979, and issued a report in March 1980, on hazardous waste disposal. Among other matters, the Senate subcommittee documented toxic waste sites in Arkansas, Michigan, Maine, and Minnesota and examined EPA’s failure to implement statutory requirements related to identifying toxic substances, preventing unsafe disposal practices, and producing a comprehensive inventory of facilities and sites with toxic wastes. The subcommittee investigation was led by Sen. Carl Levin, Democrat from Michigan and Sen. Bill Cohen, Republican from Maine.

In May 1980, the House oversight subcommittee, led by chair Eckhardt and ranking member Lent, held still another hearing on Love Canal, conducting this one jointly with the House Subcommittee on Environment, Energy, and Natural Resources of the Government Operations Committee. The environment subcommittee was led by Rep. Toby Moffett, Democrat from Connecticut and Rep. Paul McCloskey, Jr. Republican from California. The joint hearing examined the health studies and relocation efforts at Love Canal.

Rep. John LaFalce, the Democrat who represented Love Canal residents in Congress, testified about the state and federal governments’ failures to adequately address the disaster, particularly in health testing. He reported that, “We have witnessed confrontation – confrontation between the Environmental Protection Agency and the New York State Department of Health, confrontation between the White House and the Governor’s mansion. All of this, Mr. Chairman, has been at the expense of my people.”[34]

EPA officials also testified about health studies that had been performed, particularly a then-recent study, the results of which had been leaked over the weekend and caused a panic among Love Canal residents. EPA admitted that the study did not have a scientific basis and that the agency was struggling with inadequate funding and authority.[35]

The following day, May 21, 1980, President Carter issued a second emergency declaration adding 350 more acres to the Love Canal Emergency Declaration Area. Congress eventually allocated $20 million in federal funds and matching state funds to purchase homes from the 700 families that had not yet been relocated but wished to leave, and most did.[36]

On December 3, 1980, after lengthy negotiations involving multiple bills and many members, Congress enacted legislation creating what is now called the Superfund. The bipartisan legislation was the product of negotiations led by Democrat Rep. James Florio of New Jersey, Democrat Mario Biaggi of New York, Republican Rep. Gene Snyder of Kentucky, Republican Sen. Robert Stafford of Vermont, and Democrat Sen. Jennings Randolph of West Virginia.

The Superfund law, formally known as the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA), passed the Senate on a vote of 78 to 9 and the House by a vote of 274-94. It was signed into law by President Carter on December 11, 1980. Among other provisions, the law:

- Required EPA to create a list of at least 400 “top priority” hazardous waste sites for cleanup;

- Created a $1.6 billion fund for hazardous substance cleanup, of which 86% would come from taxes assessed on chemical companies producing one or more of 45 listed substances;

- Specified that the “Superfund” would pay for 90% of cleanup operation and maintenance costs at waste sites (the state paying the other 10%), loss of natural resources, and health studies for victims;

- Authorized the President to order emergency cleanups and removals of hazardous substances;

- Applied the law to a broad spectrum of toxic releases including “any spilling, leaking, pumping, pouring, emitting, emptying, discharging, injecting, escaping, leaching, dumping, or disposing” of a toxic substance into the environment;[37]

- Required companies with hazardous waste disposal sites to disclose the location and any releases to the government or face penalties; and

- Imposed fines on facilities that failed to immediately notify federal agencies of hazardous substance releases or that falsified or destroyed required records.

In response to the law, EPA designed the Hazard Ranking System “to assess the relative potential of sites to pose a threat to human health or the environment” and used the system to identify and rank sites on the National Priorities List (NPL). Love Canal became the first NPL location subjected to a Superfund cleanup.

Since enactment, the Superfund law has been amended many times, including experiencing a 1995 lapse and 2022 revival of the industry tax that helped pay for toxic cleanups. As of October 2022, EPA has identified 40,000 Superfund sites across the country, of which more than 1,300 are on the NPL. Since 1980, about 450 sites have been remediated and removed from the NPL, because they no longer pose a threat to public health.[38] Love Canal was removed from the NPL in 2004.[39]

Congress’ investigation of the Love Canal tragedy focused national attention on a hidden but burgeoning number of hazardous waste sites poisoning American communities across the country. The facts uncovered by the oversight investigation convinced members of Congress on both sides of the aisle to enact tough reforms needed to compile a comprehensive list of problem sites, prioritize those sites for cleanup, hold polluters accountable for a portion of the cleanup costs, and initiate site remediation. Although much remains undone, the Superfund investigation marks a major advance in U.S. safeguards seeking to protect American families from industrial toxic wastes that threaten both public health and the environment.

Learn More

- Superfund (EPA)

- Love Canal: A Legacy of Doubt (New York Times Retro Report)

- Love Canal Collections (University at Buffalo University Archives)

- Love Canal: Public Health Time Bomb (New York State Department of Health)

- Love Canal (Center for Health, Environment, and Justice)

Hearings by the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce:

[1] Department of Health. (2005, October). Love Canal: A special report to the Governor & Legislature: April 1981. New York State. https://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/investigations/love_canal/lcreport.htm

[2] Kleiman, J. (n.d.). Love Canal: A brief history. The State University of New York College at Geneseo. https://www.geneseo.edu/history/love_canal_history

[3] Brown, M.H. (1983). Laying waste: The poisoning of America by toxic chemicals. Random House, Inc., p. 10.

[4] Nailor, M.G., Tarlton, F., & Cassidy, J.J. (Eds.). (1978). Love Canal: Public health time bomb. New York State Department of Health. https://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/investigations/love_canal/docs/lctimbmb.pdf, p. 4.

[5] Greene, R. (2013, April 16). From homemaker to hell-raiser in Love Canal. The Center for Public Integrity. https://publicintegrity.org/environment/from-homemaker-to-hell-raiser-in-love-canal/

[6] Doršner, K. (2021). Case study: The Love Canal disaster. In M.R. Fisher (Eds.), Environmental biology. Open Oregon Educational Resources. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/envirobiology/chapter/6-4-case-study-the-love-canal-disaster/

[7] Beck, E. C. (1979, January). The Love Canal tragedy. US Environmental Protection Agency. https://archive.epa.gov/epa/aboutepa/love-canal-tragedy.html

[8] Nailor, M.G., Tarlton, F., & Cassidy, J.J. (Eds.). (1978). p. 3.

[9] Nailor, M.G., Tarlton, F., & Cassidy, J.J. (Eds.). (1978). p. 14 – 15.

[10] Hazardous waste disposal (part 1): Hearings before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, 96th Cong. (1979). https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000013564612, p. 139.

[11] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 1), 1979, p. 27.

[12] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 1), 1979, p. 61.

[13] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 1), 1979, p. 141 – 142.

[14] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 1), 1979, p. 176.

[15] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 1), 1979, p. 1.

[16] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 1), 1979, p. 1 – 2.

[17] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 1), 1979, p. 33.

[18] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 1), 1979, p. 21 – 25.

[19] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 1), 1979, p. 301 – 302.

[20] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Oil and Special Materials Control Division. (1980, August). Valley of the Drums, Bullitt County, Kentucky. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31822024241176

[21] Hazardous waste disposal report, 1979, p. 2.

[22] Hazardous waste disposal report, 1979, p. 2.

[23] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 1), 1979, p. 346.

[24] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 1), 1979, p. 346 – 347.

[25] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 2): Hearings before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, 96th Cong. (1979). https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000013564629, p. 1288.

[26] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 2), 1979, p. 1295.

[27] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 2), 1979, p. 1302 – 1303.

[28] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 2), 1979, p. 1539.

[29] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 2), 1979, p. 1591.

[30] Hazardous waste disposal hearings (part 2), 1979, p. 1597.

[31] Hazardous waste disposal report, 1979, pp. 3-5.

[32] Hazardous waste disposal report, 1979, pp. 66, 70.

[33] Hazardous waste disposal report, 1979, p. 55 – 60.

[34] Love Canal, 1980, p. 5.

[35] Love Canal, 1980, p. 17.

[36] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2022, September 28). Love Canal, Niagara Falls, NY cleanup activities. Superfund sites. https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.cleanup&id=0201290

[37] Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, Publ. L. No. 96-510, 94 Stat. 2767 (1980). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-94/pdf/STATUTE-94-Pg2767.pdf

[38] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2022, March 11). Superfund: National Priorities List (NPL). Superfund. https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-national-priorities-list-npl

[39] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2022, September 28).