Portraits in Oversight:

Abraham Ribicoff and the Traffic Safety Hearings

Abraham Ribicoff led a Senate oversight investigation that not only fundamentally changed how the federal government handled motor vehicle safety problems, but also helped save millions of lives.

Senator Ribicoff, a Democrat, represented the state of Connecticut from 1963 to 1981. He’d previously served the Constitution State in the U.S. House of Representatives and then as its governor and was President John F. Kennedy’s Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare from January 1961 to July 1962. Once in the Senate, he joined the Senate’s leading investigative body, the Committee on Government Operations, later renamed the Committee on Governmental Affairs. He served as the committee chair from 1975 to 1981.

One of his key investigations was a year-long inquiry which began in 1965, before he became committee chair, into the issue of traffic safety. In the United States, between 1900 and 1964, motor vehicle accidents caused 1.5 million deaths. In 1965 alone, with 91 million vehicles on American roads, accidents accounted for:

- 49,000 deaths;

- 6 million non-fatal injuries, with 1.8 million leading to disabilities;

- Lost wages totaling an estimated $2.2 billion;

- Property damage estimated at $2.8 billion;

- Medical expenses exceeding $500 million; and

- Overhead insurance costs of $2.6 billion.[1]

The federal government had issued safety regulations for railroads, airplanes, and marine transportation, but left motor vehicle safety laws to the states. However, state laws were often poorly drafted and outdated, and more than half the states had no laws at all on vehicle inspection. Auto companies had long contended that drivers and road conditions, not cars, were responsible for accidents, and states had bowed to that claim despite growing evidence of vehicles that were inherently unsafe as designed.

Senator Ribicoff first attracted national attention to the issue when he championed traffic safety programs as Governor of Connecticut and Chair of the Governor’s Conference Special Committee on Highway Safety. His chance to bring the issue center-stage in the Senate came in 1965, when President Lyndon Johnson proposed a bill to authorize federal motor vehicle safety standards within six years. Expecting Congress to object, the administration was surprised when it was instead challenged on the bill’s lengthy timeline which failed to require new safety features before 1970’s models. Senator Ribicoff asked, “Are we going to watch 50 million new cars roll off the assembly lines free of any safety regulation?”

Senator Ribicoff launched his investigation into the “Federal Role in Traffic Safety” as chair of the Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization. Subcommittee members included Democratic Senators John McClellan of Arkansas; Ernest Gruening of Alaska; Robert Kennedy of New York; Fred Harris of Oklahoma; and Joseph Montoya of New Mexico; and Republican Senators Jacob Javits of New York; Milward Simpson of Wyoming; and Carl Curtis of Nebraska. The investigation had strong bipartisan support throughout.

At the first hearing on March 22, 1965, Senator Ribicoff emphasized in his opening statement:

“There is no doubt that since the invention of the internal combustion engine we have practiced an unbelievable form of national self-destruction. In the past minute 20 accidents have taken place. One-half hour from now three Americans will be dead who right now are alive. … The manner in which the Federal Government is carrying out its responsibility is of vital importance to the overall national effort to reduce traffic accidents. It can lead and give proper direction – or it can foot-drag and stagnate. We will determine if the latter now exists and make certain the former becomes a reality.”

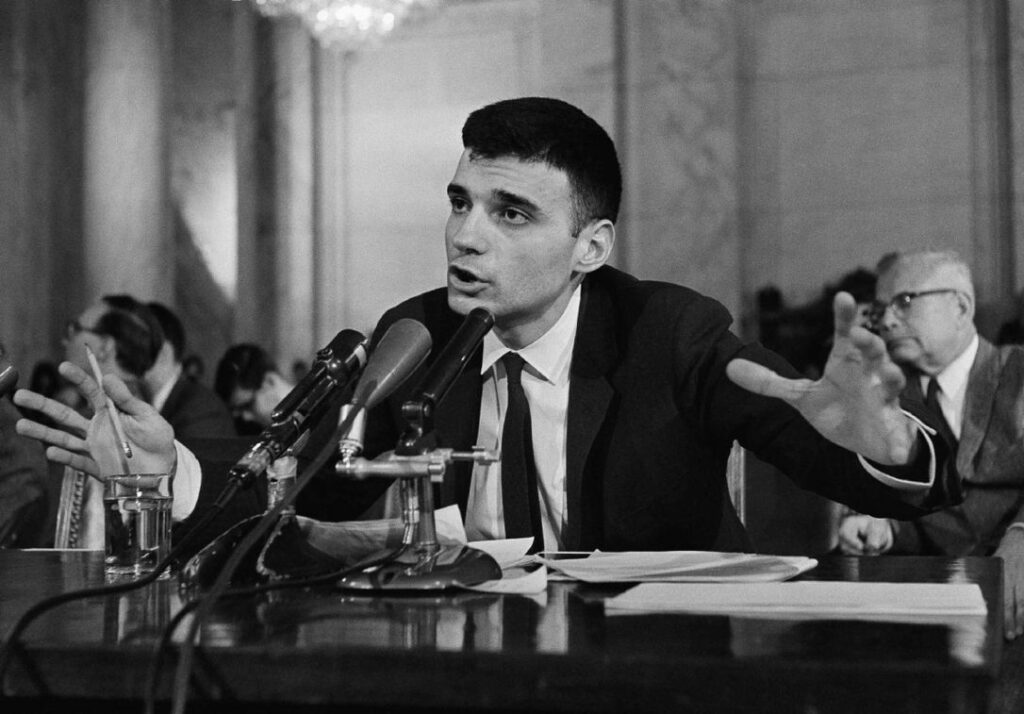

To aid in its fact-finding mission, the subcommittee employed lawyer and consumer protection advocate Ralph Nader as an unpaid consultant. At the time, Mr. Nader was writing a book detailing American car manufacturers’ resistance to including safety features in car designs. Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile was published in November 1965, and Senator Ribicoff called on Mr. Nader to testify before the subcommittee in February 1966. Though the Nader book initially met with little fanfare, it became a best-seller when it was revealed during a subsequent subcommittee hearing that General Motors (GM) had hired a private detective agency to tail Mr. Nader.

James Roche, GM CEO and Board Chair, when called to testify before the subcommittee in March 1966, admitted and apologized for the scheme. Robert A. Lutz, a senior GM executive during the 1960s hearings, admitted 50 years later, “The book had a seminal effect. I don’t like Ralph Nader and I didn’t like the book, but there was definitely a role for government in auto safety.”

The Ribicoff subcommittee held 11 hearings between March 1965 and March 1966, questioning 46 witnesses, presenting 152 exhibits, and producing 1,600 pages of testimony. Its work led directly to introduction of S. 3005, a bill to establish safety standards for motor vehicles used in interstate commerce. The Committee on Commerce, led by Senator Warren Magnuson, held seven hearings on the bill and heard from another 40 witnesses.

Better known as the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966, S. 3005 passed the Senate 76 to 0 and the House 365 to 0. Much more rigorous than the bill originally proposed by the administration, it was signed into law by President Johnson on September 9, 1966. Its sweeping new safety regulations included:

- Requiring the Secretary of Commerce to issue motor vehicle safety standards, and requiring state safety standards to be identical or stronger;

- Prohibiting the sale of vehicles that did not meet the new safety standards;

- Allowing Commerce agents to enter and inspect any vehicle manufacturing plant and to obtain safety documentation;

- Requiring manufacturers to notify Commerce and vehicle purchasers of safety defects and how to address them;

- Requiring federal research and testing with results made public;

- Requiring an annual report to Congress with accident statistics, data on compliance with federal standards, and other key information; and

- Authorizing monetary penalties for safety violations and other misconduct.

The same day, President Johnson also signed the Highway Safety Act, which had originated in the House and also enjoyed widespread bipartisan support, passing in that chamber by a vote of 318 to 3. It required the Secretary of Commerce to create a uniform highway safety program for the states and allowed the states to use federal funds to implement programs involving licensing, vehicle inspection, vehicle registration, accident prevention and investigation, and more. At the signing ceremony in the White House Rose Garden, President Johnson remarked: “The automobile industry has been one of our Nation’s most dynamic and inventive industries. I hope, and I believe, that its skill and imagination will somehow be able to build in more safety – without building on more costs. For safety is no luxury item, it is no optional extra; it must be a normal cost of doing business.”

Shortly after the law was enacted, the Department of Transportation Act was signed on October 15, 1966, creating the Department of Transportation and transferring the responsibilities outlined in the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act and Highway Safety Act to the new department. New motor vehicle safety standards established as a result of the Ribicoff investigation and the new laws included shoulder-lap seatbelts, protective dashboards, dual braking systems, safety door latches, collapsible steering columns, and shatterproof windshields. In 2015, the Center of Auto Safety credited the legal changes with reducing motor vehicle deaths by 80%, saving more than 3.5 million lives between 1966 and 2014.

Senator Ribicoff conducted many other important investigations and became a revered figure for colleagues on both sides of the aisle. His work included inquiries into issues related to arms control, civil rights, international trade, civil service reform, toxic pesticides, and the need for federal program audits. But his role in the traffic safety investigation remains a shining example of how congressional investigations can focus public attention on a glaring problem, generate momentum for reforms, and improve the lives of average Americans.

[1] Hearings on the Federal Role in Traffic Safety Before the Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization of the Senate Committee on Government Operations, 89th Congress, 2nd Session, part 3, p. 1105 (1966).