Portraits in Oversight:

Congress and the Enron Scandal

On December 2, 2001, despite claiming assets in excess of $60 billion and revenues exceeding $100 billion, Enron Corp. filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, becoming the then-largest bankrupt corporation in U.S. history. The resulting economic dislocation sparked one of most extensive bipartisan, bicameral oversight efforts by Congress in years, eventually leading to landmark legislation.

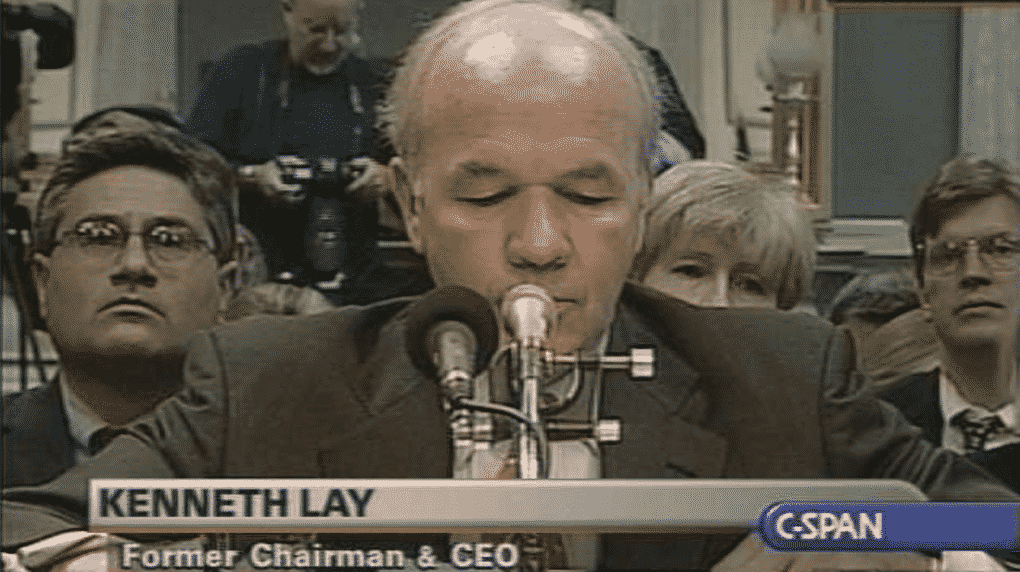

Founded in 1985 by Kenneth Lay, the Houston-based energy company rose to become the seventh largest publicly traded corporation in the United States by 2001, having been named Fortune magazine’s “Most Innovative Company in America” six years in a row. Enron’s demise was triggered by sharp losses as well as allegations of accounting fraud. As the company unraveled, its 25,000 employees lost their jobs as well as $2 billion in pension savings and $1.2 billion in retirement funds.[1] Arthur Andersen LLP, Enron’s auditor and one of the largest accounting firms in the world, was so marred by its role in the scandal that it, too, went out of business, putting 28,000 employees out of work.[2] Enron’s many creditors also suffered as the company stopped paying its bills.

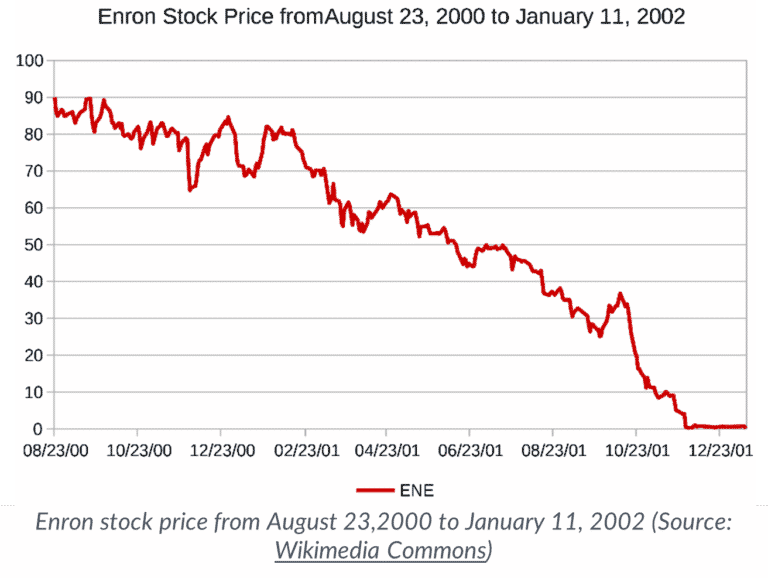

In turn, Enron’s 59,000 stockholders, including many pension funds, lost virtually their entire investments when the company’s stock price nosedived. It fell from a high of $90 on August 17, 2000, to $20 on October 22, 2001, when the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) announced an investigation, to $0.26 on November 30, 2001.[3] As one stock analyst observed, “It had taken Enron 16 years to go from about $10 billion of assets to $65 billion of assets, and it took them 24 days to go bankrupt.”

The economic fallout from Enron’s bankruptcy was so far-reaching that multiple House and Senate committees opened investigations into a variety of aspects of the scandal. Issues included accounting fraud, self-dealing, excessive executive pay, auditing failures, pension mismanagement, energy price manipulation, secretive offshore dealings, and corporate tax dodging, as well as why government agencies had failed to prevent, detect, or counter the wrongdoing.

As the inquiries unfolded, congressional leadership in both chambers pursued the Enron scandal in a sustained, bipartisan fashion. Committees churned out numerous hearings and reports, addressing a wide range of sometimes overlapping concerns. Their work included the following:

- The House Committee on Education and the Workforce concentrated on the collapse of Enron’s employee retirement and pension plans, and whether the company violated the Employee and Retirement Income Security Act of 1974.

- The House Committee on Energy and Commerce focused on accounting and governance issues including self-dealing by Enron’s senior officers, misleading accounting, auditing failures, lax accounting and auditing standards, poor oversight by Enron’s Board of Directors, and poor self-governance by the auditing profession.

- The House Committee on Financial Services examined the impact on U.S. capital markets, including reduced confidence in corporate financial statements, Enron’s use of structured finance and complex accounting to overstate its financial results, and lax regulation by the SEC and Financial Accounting Standards Board.

- The Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs held a long series of hearings scrutinizing the role of Arthur Andersen in facilitating Enron’s accounting fraud, including the misuse of certified financial audits, lax accounting and auditing standards, auditing failures, poor detection of financial fraud at publicly traded corporations, the U.S. accounting profession’s failure to police its own members, and inadequate supervision by the SEC.

- The Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation examined Enron’s manipulation of electricity prices in Western states using complex trading strategies called “Death Star,” “Get Shorty,” and “Fat Boy.” It also evaluated the impact that false information about the value of Enron’s stock had on consumers, investors, and employees.

- The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources probed the impact of Enron’s collapse on energy markets and energy pricing, including issues related to its interstate natural gas pipelines, operation of electrical utilities, and management of EnronOnline, a secretive electronic exchange used to trade energy futures and swaps.

- The Senate Committee on Finance examined Enron’s use of complex tax strategies to dodge paying corporate income tax in four of its last five years, despite reporting huge profits to shareholders, and its use of accounting gimmicks to hide the extent of its debt and inflate its earnings.

- The Joint Committee on Taxation produced a three-volume, 2,700-page report detailing Enron’s abusive executive compensation, pension, and tax practices, including formation of 3,500 domestic and offshore entities (441 in the Cayman Islands alone) and a dozen abusive tax shelters.

- The Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs analyzed the failure of government agencies, including the SEC and Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), as well as private sector actors such as credit rating agencies, Wall Street analysts, and company 401(k) managers, to detect, prevent, or expose Enron’s wrongdoing before it upended financial markets.

- The Committee’s Permanent Subcommittee of Investigations focused on how the company’s Board of Directors, investment banks, and other financial institutions helped Enron cook its books. It also delved into the complexities of Enron’s accounting, investment, and tax practices.

- The Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions examined the bankruptcy’s impact on Enron employees’ pensions and the oversight and enforcement role of the Department of Labor.

- The Senate Committee on the Judiciary examined loopholes in federal liability laws, including in the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act, that appeared to be shielding accountants, auditors, and law firms from being held accountable for aiding and abetting Enron’s misconduct.

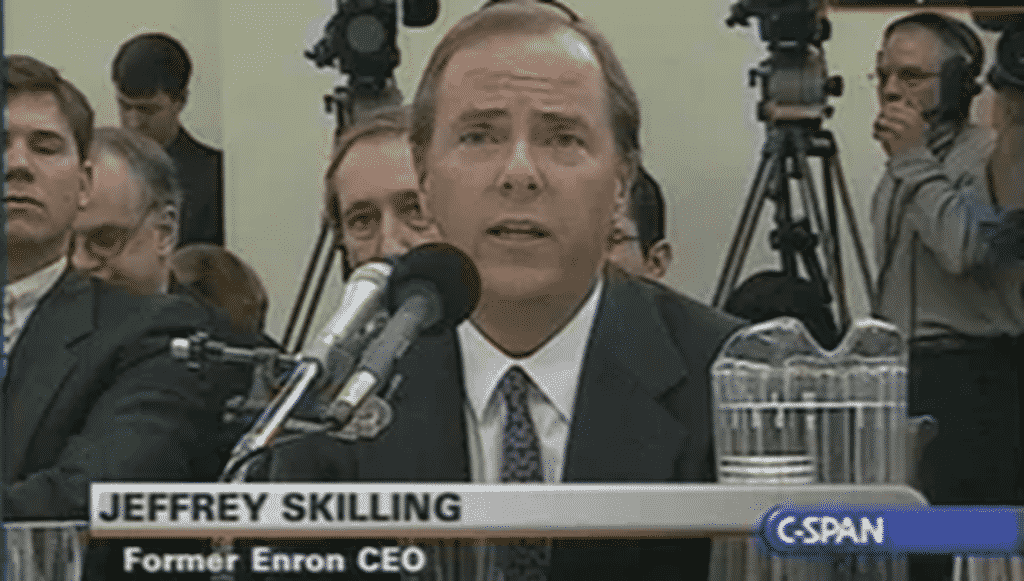

The earliest congressional hearings took place about two weeks after Enron’s bankruptcy. The first was on December 12, 2001, before the House Committee on Financial Services; the second on December 18, 2001, before the Senate Commerce Committee. Both hearings surveyed the mounting damage from the Enron collapse, but neither heard directly from the company. Although Enron’s Chair and founder Kenneth Lay, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Jeffrey Skilling, and Chief Financial Officer (CFO) Andy Fastow were eventually subpoenaed to testify at several congressional hearings, Mr. Lay and Mr. Fastow exercised their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination and refused to testify. In contrast, against advice of counsel, Mr. Skilling appeared before several committees, but stopped testifying after February 2002.[4]

On February 4, 2002, the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Capital Markets took testimony from William Powers, Dean of the University of Texas Law School, head of a “Special Investigative Committee” formed by Enron’s Board of Directors after the company’s collapse, and author of the “Powers Report.” That report provided important basic information about Enron and was used by several congressional committees as a starting point for their own inquiries. At the hearing, Mr. Powers testified that “what we found was absolutely appalling,” including improper actions taken by Enron executives to enrich themselves and “a systematic and pervasive attempt by Enron’s management to misrepresent the company’s financial condition.”

On February 14, 2002, the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations held a 4-hour hearing whose sole witness was Sherron Watkins, Enron Vice President of Corporate Development turned whistleblower. She testified about a letter she’d sent to Ken Lay in August 2001, warning that Enron could implode “in a wave of accounting scandals.” Despite subsequent meetings with Mr. Lay laying out the problems, Enron did nothing to curb its misleading accounting. On February 26, 2002, Ms. Watkins testified again before the Senate Commerce Committee, appearing with Enron officers Jeffrey Skilling and Jeffrey McMahon.

Later that year, under the leadership of Chair Carl Levin, Democrat of Michigan, and Ranking Member Susan Collins, Republican of Maine, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations held a series of bipartisan hearings that delved deeply into the details of Enron’s misconduct. Over the course of what turned out to be an 18-month investigation, PSI:

- issued more than 75 subpoenas;

- collected and examined over two million pages of documents;

- conducted more than 100 interviews, including of 13 Enron board members;

- issued three bipartisan reports; and

- released over 5,000 pages of testimony and exhibits over four days of hearings.[5]

The PSI investigation exposed failures and frauds on many levels at Enron and dissected a number of complex transactions, including the following:

- PSI explained how Enron “sold” poorly performing assets to a related entity called Whitewing, while secretly pledging $2.6 billion in Enron stock and promissory notes to secure the loans Whitewing took out to buy the assets. Enron failed to disclose its Whitewing pledges on its financial statements.[6]

- PSI explained how Enron used four special purpose entities, the “Raptors,” to “hedge” volatile investments held by Enron. At the same time, Enron secretly pledged its stock and stock contracts to secure the Raptors, defeating the purpose of the supposedly independent “hedges.” PSI also showed how Enron used LJM2, an entity owned by CFO Fastow, to provide initial funding of $30 million for each Raptor to establish its independence and creditworthiness, only to allow the funding to be withdrawn six months later, paying LJM2 a $10 million fee per Raptor. Enron used the Raptor “hedges” to justify omitting almost $1 billion in investment losses from its financial statements.[7]

- PSI explained how Enron “sold” three Nigerian barges (operating as floating power stations) to Merrill Lynch for $28 million, after secretly promising to find a buyer for the assets within six months and guaranteeing Merrill a fixed profit on the resale. Under generally accepted accounting rules, that type of arrangement was not a true sale, and Enron could not book the sales price as income. But Enron booked the income anyway.[8]

Documents released by PSI showed that, overall at the time of its bankruptcy, Enron had moved at least $27 billion or almost 50% of its assets off-book to related entities in an effort to hide its poorly performing assets and inflate its income.[9]

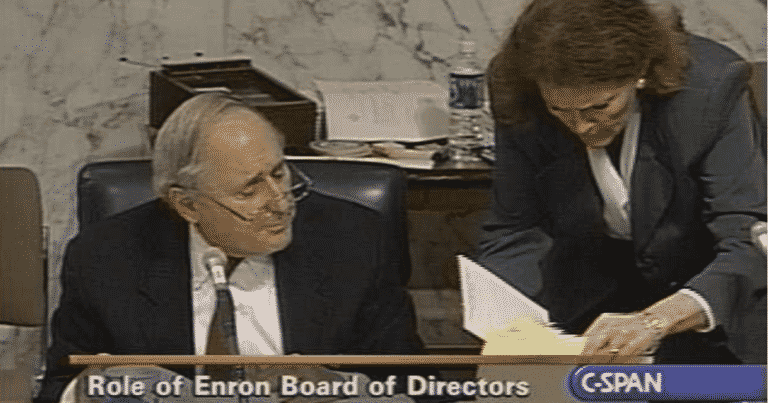

The PSI investigation also detailed the role of Enron’s Board of Directors in the company’s downfall, including the following: [10]

- PSI showed that the Board of Directors had been informed by Arthur Andersen that Enron was using high-risk accounting and extensive off-the-books activity, knowingly permitted both practices, and explicitly approved the deceptive transactions just described.

- PSI released evidence showing that the Board knew and approved of Anderson’s dual roles as Enron’s auditor and consultant, despite the obvious conflicts of interest involved in the firm’s auditing its own work and wanting to protect its substantial consulting fees.

- PSI documented Board approval of an exception to Enron’s conflict of interest policies allowing CFO Fastow to establish special-purpose entities, LJM1 and LJM2, for the express purpose of doing business with Enron. Mr. Fastow admitted to profits of at least $45 million from LJM’s dealings with Enron.[11]

- PSI disclosed Board support for Enron’s excessive executive compensation practices, including payments of $750 million in executive cash bonuses in 2000, when the company’s entire net income was $975 million.[12]

- PSI traced Board approval of Enron’s outsized executive stock option grants, including a one-year option grant valued at $123 million for Ken Lay and a set of option grants to the head of its energy services, Lou Pai, who cashed them in and sold the underlying stock for $265 million.[13]

- PSI also disclosed how the Board gave Ken Lay a company-financed line of credit, allowed him to take out $77 million in serial cash loans, and then allowed him to repay those loans with Enron stock at a time when the company was experiencing cash flow problems.[14]

- PSI completed the picture by documenting how several Enron board members enjoyed lucrative side arrangements with the company, creating conditions that made it hard for them to challenge senior management.[15]

PSI concluded that the Board had failed to safeguard Enron shareholders and had contributed to the company’s collapse by “allowing Enron to engage in high risk accounting, inappropriate conflict of interest transactions, extensive undisclosed off-the-books activities, and excessive executive compensation.”[16]

In the next stage of its inquiry, PSI disclosed Enron’s use of a series of phony “prepay” transactions to hide $8 billion in debt, each transaction of which was knowingly facilitated by a major financial institution.[17]

- PSI detailed how JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup, in particular, used offshore shell companies they secretly controlled to provide billions of dollars in cash loans to Enron, while allowing Enron to characterize the loans on its books as income from trading deals it had secured with those offshore entities. As Senator Levin explained at a July 23, 2002 hearing: “There is a big difference in the financial world between cash that comes from business activity versus cash that comes from a loan, and there is supposed to be a big difference in the accounting treatment.” He observed that Enron’s misleading accounting had characterized the prepays as an increase in business activity when they really represented an increase in debt.

- PSI released emails showing that the financial institutions knew exactly what was going on. For example, in one email, a JPMorgan Chase banker wrote: “Enron loves these deals as they are able to hide funded debt from their equity analysts because they (at the very least) book it as deferred rev[enue] or (better yet) bury it in their trading liabilities.”

- PSI also showed that after Citigroup extended $2.4 billion in prepays to Enron, the bank ensured the loans were repaid by selling investors bonds issued by an Enron-related shell entity, Yosemite, without disclosing that the funds would primarily be used to repay Enron’s debt to Citigroup.

PSI showed that if the phony prepays had been treated as debt on Enron’s 2000 financial statement, its debt level would have jumped from $10 billion to $14 billion, a 40% increase. Instead, neither Enron nor its bankers disclosed the company’s true level of indebtedness.

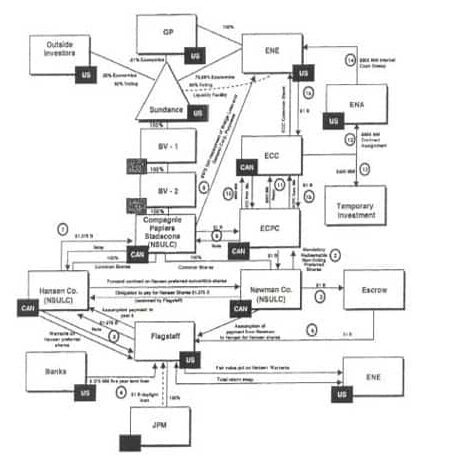

Finally, PSI documented four inter-connected “structured finance” transactions that were part of an Enron venture involving pulp and paper assets. The facts showed that they were used not only to inflate Enron’s income, but also to dodge millions of dollars in tax liabilities.[18]

- PSI detailed three of the Enron transactions known as Fishtail, Bacchus, and Sundance, showing how they “involved a series of inter-related asset sales to special purpose entities and joint ventures, complete with inflated asset values, hidden Enron guarantees, and sham third party investments.”[19]

- PSI also exposed a 2001 transaction called Slapshot which involved a fake $1 billion loan facilitated by JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup moving through a series of shell entities and bank accounts to generate millions of dollars in phony tax deductions.

Through its hearings and reports, PSI helped policymakers, law enforcement, private sector professionals, and the public gain a deeper understanding of exactly how Enron had bent the rules.

Concurrent with the congressional inquiries, multiple federal agencies launched their own criminal and civil investigations into Enron’s actions, including the Department of Justice (DOJ), Department of Labor, SEC, CFTC, FERC, and Internal Revenue Service. DOJ took the lead in a multi-agency Enron Task Force which, among other actions:

- conducted 1,800+ interviews;

- collected 3,000+ boxes of evidence and 4+ terabytes of data;

- seized $164 million;

- obtained $90 million for victim compensation; [20] and

- secured over 30 criminal convictions.[21]

The criminal conviction record for Enron’s most senior officers was mixed. Enron’s founder, Ken Lay, was convicted by a jury on ten charges including bank fraud and conspiracy to commit securities and wire fraud. However, he died of a heart attack while appealing his case, and his conviction was vacated due to the incomplete appeal.[22]

Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling was convicted on 19 counts of securities and wire fraud and sentenced to 24 years in prison. But he later managed to reduce his sentence by ten years by agreeing to forfeit $42 million and end his legal appeals. After entering prison on December 13, 2006, he was released on February 21, 2019.[23]

Enron CFO Andrew Fastow was indicted on 98 counts of criminal misconduct including conspiracy, money laundering, fraud, and insider trading. Ultimately, he pled guilty to two counts of conspiracy and agreed to testify against Mr. Lay and Mr. Skilling. He spent six years in prison.[24]

Arthur Andersen was convicted by a jury of obstruction of justice stemming from its destruction of Enron-related documents. In 2002, Andersen surrendered its CPA license and went out of business. Three years later in 2005, however, the Supreme Court reversed the conviction, ruling the jury instructions failed to state the evidence had to prove Andersen knew it was engaged in wrongdoing. By then, the firm was gone, but the lead Andersen auditor of Enron, David Duncan, responded by withdrawing his guilty plea and avoiding imprisonment.

Three Enron energy traders, Timothy Belden, John Forney, and Jeffrey Richter, pled guilty to charges related to manipulating energy prices in California. But all three avoided prison, instead receiving minimal sentences consisting of two years of probation.

Enron itself was never convicted of a crime. Instead, the bankruptcy, a host of civil enforcement actions, and multiple civil lawsuits brought by its many victims dragged on for years, slowly draining Enron’s remaining assets.[25]

At a 2002 hearing, Senator Collins offered a valuable reminder about the importance of congressional oversight, even in cases with extensive criminal and civil investigations:

Unraveling the complexities of what happened, determining who is responsible, and prosecuting those individuals will take the Department of Justice, the Labor Department, and the Securities and Exchange Commission many months and possibly years. The Subcommittee’s job is not to duplicate those efforts, but rather to examine the actions taken by all of the players who contributed to Enron’s demise in order to illuminate the public policy issues. By doing so, the Subcommittee can help focus the debate in Congress, in State legislatures, and in corporate board rooms across the Nation on what measures should be taken and by whom to minimize the chances of another Enron-like debacle.[26]

The Enron investigations did produce landmark legislation. Most important was the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which imposed sweeping changes on U.S. corporate governance, accounting, and financial practices. Named for its lead sponsors, Democratic Senator Paul S. Sarbanes of Maryland and Republican Representative Michael G. Oxley of Ohio, the so-called “SOX” Act passed the House by a vote of 423 to 3, and the Senate by a vote of 99 to 0, and was signed into law by President George W. Bush on July 30, 2002.[27] Among other provisions, the law:

- Required the chief executive officer and chief financial officer of a publicly traded corporation to personally certify that their company’s financial statements accurately presented its financial condition, under threat of fines and prison time for misrepresentations;

- Created the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board and required all auditors of publicly traded corporations to register with the board, adhere to its standards, and undergo annual examinations of their auditing practices;

- Required the board of directors of a publicly traded corporation to establish an auditing committee with accounting experts to review the company’s financial statements and accounting practices;

- Required auditors to ensure that each publicly traded corporation established the internal controls needed to ensure the integrity of its financial reports;

- Banned corporations from using corporate funds to finance loans to senior managers and corporate insiders; and

- Prohibited auditors from providing both auditing and consulting services to the same publicly traded corporation in order to prevent conflicts of interest from impairing the auditor’s review of the corporation’s financial reports.

In addition, after a long battle, Congress passed legislation to close what it called the “Enron loophole,” a provision enacted at Enron’s urging in 2000, that barred federal oversight of electronic energy trading exchanges when trading was limited to large corporations. The reasoning had been that the large firms could look out for themselves and didn’t need government supervision. But Congress determined post-Enron that energy markets needed a federal cop on the beat – not to protect the traders – but to protect the public from price manipulation, excessive speculation, and other trading abuses. In 2008, Congress finally enacted a set of provisions enabling the CFTC to police all energy trading exchanges.[28] Together, those two laws represented significant change, even as many other reforms stalled.

Senator Levin once explained at a hearing why so many in Congress felt compelled to engage in a herculean effort to investigate Enron’s collapse:

The Enron debacle has stirred the passions of Americans nationwide. The deceptions and the accounting gimmicks, the shredding of documents that have occurred shake the very foundation of our confidence in corporate America. What a travesty. Enron’s management made out like bandits, while tens of thousands of average people saw their savings, retirement funds or jobs go down the drain. … Enron’s abrupt collapse from corporate star to disgraced bankrupt is crucial for all of us to understand, because each and every American’s future is tied to the success or failure of corporate America. Publicly traded companies employ millions of Americans. They are key to U.S. international competitiveness. Over half of all U.S. households are now investing in American capital markets, placing their hopes for a college education for their children, quality care for their parents, and adequate money for their retirement, in the hands of our publicly traded companies. … The legislative effort that is needed to turn this travesty into a positive force, to clean up some long-festering problems in U.S. corporate governance and accounting practice will require a sustained effort from all of us.[29]

Enron did, in fact, spur Congress to a sustained, bipartisan, bicameral oversight effort that was remarkable in its time and still resonates today as a case study of how Congress can analyze and respond to complex financial wrongdoing with important legislative reforms.

Learn More

- Timeline: A chronology of Enron Corp.

- Enron: A Select Chronology of Congressional, Corporate, and Government Activities (March 18, 2003) by the Congressional Research Service

- The Smartest Guys in the Room: The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron by Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind

- Twenty Years Later: The Lasting Lessons of Enron

For more information on the Permanent Subcommittee of Investigations hearings and reports:

- Hearing: The Role of the Board of Directors in Enron’s Collapse

- Report: The Role of the Board of Directors in Enron’s Collapse

- Hearing: The Role of the Financial Institutions of Financial Institutions in Enron’s Collapse (Volume 1)

- Hearing: The Role of the Financial Institutions of Financial Institutions in Enron’s Collapse (Volume 2)

- Hearing: Oversight of Investment Banks’ Response to the Lessons of Enron (Volume 1)

- Hearing: Oversight of Investment Banks’ Response to the Lessons of Enron (Volume 2)

- Report: Fishtail, Bacchus, Sundance, and Slapshot: Four Enron Transactions Funded and Facilitated by U.S. Financial Institutions

- [1] Gibney, A. (2005). Enron: The smartest guys in the room [film]. 2929 Entertainment, HDNet Films, & Jigsaw Productions.

- [2] Arthur Anderson goes out of business. (2002, August 31). ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Business/Decade/arthur-andersen-business/story?id=9279255

- [3] University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School. (2021). Enron historical stock price. http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/enron/enronstockchart.pdf

- [4] McLean, B., & Elkind, P. (2003). The smartest guys in the room: The amazing rise and scandalous fall of Enron. Portfolio Trade.

- [5] Fishtail, Bacchus, Sundance, and Slapshot: Four Enron Transactions Funded and Facilitated by U.S. Financial Institutions. S. Rep. No. 107-82 (2003)(hereinafter “Fishtail Report”), at 2. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-107SPRT83559/pdf/CPRT-107SPRT83559.pdf

- [6] The role of the board of directors in Enron’s collapse.” Report by the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee of Investigations, 107th Cong. (2002)(hereinafter “Board of Directors Report”), at 36-39. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-107SPRT80393/pdf/CPRT-107SPRT80393.pdf

- [7] Id. at 40-47.

- [8] The Role of the Financial Institutions in Enron’s Collapse-Volume 1, hearing by the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee of Investigations, 107th Cong. (July 23 & 30, 2002)(hereinafter “Financial Institution Hearing”), at 163-164, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-107shrg81313/pdf/CHRG-107shrg81313.pdf.

- [9] Board of Directors Report, at 36.

- [10] See Board of Directors Report.

- [11] Id., at 24-26, 34.

- [12] Id., at 51.

- [13] Id., at 49.

- [14] Id., at 49-50.

- [15] Id., at 52.

- [16] Id., at 3.

- [17] See Financial Institutions Hearing.

- [18] See Fishtail Report.

- [19] Bean, Elise (2018). Financial Exposure: Carl Levin’s Senate Investigations of Finance and Tax Abuse, at 113.

- [20] Federal Bureau of Investigation. (n.d.) Enron. Famous Cases & Criminals. https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/enron

- [21] The defendants of the Enron era and their cases. (2011, November 25). Chron.com. https://www.chron.com/business/article/The-defendants-of-the-Enron-era-and-their-cases-2293378.php

- [22] Federal judge vacates fraud conviction of Enron’s former chairman Kenneth Lay. (2006, October 19). Global Power Report.

- [23] Associated Press. (2006, May 25). A look at those involved in Enron Scandal. Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/sns-ap-enron-trial-glance-story.html

- [24] Associated Press, 2006.

- [25] Sumoski, D. M. (2007, April). Enron: Navigating the civil side of the corporate case of the century. ABA Section of Litigation of Annual Conference. https://www.ccsb.com/pdf/Publications/Business%20Litigation/Navigating_the_civil_side.pdf

- [26] The role of the board of directors in Enron’s collapse: Hearing before the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee of Investigations, 107th Cong. (2002). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-107shrg80300/pdf/CHRG-107shrg80300.pdf

- [27] Bottiglieri, W. A., Reville, P. J., & Grunewald, D. (2009). The Enron collapse – the aftershocks. Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics, 1-9.

- [28] Congress approves measure to close ‘Enron Loophole.’ (2008, May 15). Senator Dianne Feinstein. https://www.feinstein.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?ID=ed7c8fe7-d420-e683-c889-bb53106f90f3

- [29] The fall of Enron: How could it have happened? Hearing before the U.S. Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs, 107th Cong. (2002). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-107shrg78614/pdf/CHRG-107shrg78614.pdf